Research Article - (2022) Volume 12, Issue 6

This study was conducted to determine the knowledge, attitude and willingness to interact with mentally ill people among in school adolescents. Participants of the study comprised of 359 adolescents who were in secondary and preparatory schools in the four Wollega zonal towns in the year 2019. From each four Wollega zonal towns, two schools (one secondary and one preparatory) were randomly selected; hence, 4 secondary and 4 preparatory schools were included in the study. The survey consisting of three measures constructed to assess adolescents’ knowledge, attitude, and willingness to interact with mentally ill people were adapted and used. Descriptive statistics, mainly frequency and percentage were used in the analysis. The result revealed in school adolescents’ knowledge of mental illness is inconsistent. They were informed well about the inappropriate treatment and representation of people with mental illnesses. However, their knowledge is poor in other areas. Attitudes expressed toward mentally ill people among these adolescents were also mixed; some of the adolescents expressed accepting, respectful, and sympathetic views toward people with mental illness. Still large proportions of the adolescents were fearful of approaching and being a friend of mentally ill person. Social distance results revealed positive attitude by majority of the respondents and less accepting views by a few of them. It is therefore recommended that the four Wollega Zonal town health offices need to educate adolescents regarding specific disorders and about acceptance of individuals with mental illness.

Knowledge about mental illness • Attitude towards mentally ill people • Willingness to interact with a person with a mental illness • In school Adolescents

Health is defined by different scholars and organizations differently. For instance, WHO (2001) viewed health as a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely absence of disease or infirmity [1-3]. Yet, added the spiritual aspect and defined health as state of complete physical, mental, spiritual and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity.

In particular, WHO (2011) defines mental health as a state of well-being in which every individual realizes his or her own potential, can cope with the normal stresses of life, can work productively and fruitfully, and is able to contribute to his or her community i.e. a person is said to be mentally healthy if he/ she is able to cope with stressors of life and can make rational decisions concerning his/her daily life. Likewise, explained that mental illness is a medical condition that disrupts a person’s thinking, feeling, experience, emotions, mood, ability to relate to other and daily functioning or it is a functional impairment in people, making it more difficult for them to sustain interpersonal relationships and carry on their jobs, and sometimes leading to self-destructive behaviors and even suicide. In social or cultural view, an individual is seen as ‘mentally ill’ when he/she is unable to find a sense of purpose, harmony and health in their surrounding [4-6].

WHO (2001) reported that the impact of mental health problem is rising globally. The world health organization drew attention to the growing global burden of mental disorders. Current estimates comprised 12% of the global burden of disease and estimated to rise to 15% by the year 2020, which would then make them the second leading cause of health disability in the world. This burden is thought to be worse in low income countries where poverty and other communicable diseases abounds. It is gradually recognized that mental illnesses are public health problems throughout the world in developing as well as developed countries. Furthermore, depression is currently the leading cause of non-fatal burden when considering all mental and physical illnesses, accounting for approximately 10% of total years lived with disability in low and middle income countries [7-12].

Moreover, revealed that 154 million people globally suffered from depression, 25 million people from schizophrenia, 91 million people from alcohol use disorders, and 15 million from drug use disorders. Nearly 25% of individuals, in both developed and developing countries develop one or more mental or behavioral disorders at some stage in their life (WHO, 2001).

Of all the health problems, mental illnesses are poorly understood by the general public. Such poor knowledge and negative attitude towards mental illness threatens the effectiveness of patient care and rehabilitation. This poor and inappropriate view about mental illness and negative attitude towards the mentally ill can inhibit the decision to seek help and provide proper holistic care. Better knowledge is often reported to result in improved attitudes towards people with mental illness and a belief that mental illnesses are treatable, can encourage early treatment seeking and promote better outcomes [13-19].

Mentally ill people are labeled as “different” from other people and are viewed negatively by others. Many studies have demonstrated that persons labeled as mentally ill are perceived with attributes that are more negative and are more likely to be rejected regardless of their behavior [20,21]. Mental illnesses are among the most stigmatizing conditions worldwide. In the context of mental illness, stigma is seen as a construct associated with lack of knowledge, negative attitudes, and avoiding behavior towards a mentally ill people. People with mental illness are perceived as dangerous, unpredictable, unattractive, and unworthy and are unlikely to be productive members of their communities. These perceptions lead to their exclusion from the community. Therefore, they are challenged not only by their illness but also by the stigma and stereotypes associated with them by the community.

According to, it is unlikely that these negative attitudes and misperceptions emerge full blown in adulthood; rather, they are likely to have their roots in childhood and develop gradually through adolescence. Psychiatrically labeled children, then, may face misunderstandings and negative attitudes by their peers. Ostracism, rejection, teasing, and damage to self-esteem, as well as reluctance to seek or accept mental health treatment, are among the possible consequences.

These consequences may be particularly relevant during adolescence and preadolescence, a period in which onset of a variety of psychiatric disorders peaks and children are acutely attuned to the judgments of their peers. Accordingly, it is important to understand more about the knowledge and attitude of adolescents related to mental illnesses and mentally ill people.

However, in Ethiopia, where malnutrition and preventable infectious diseases are very common, mental health problems, which are regarded as non-life threatening problems, have not received much research attention. Yet, mental health problems account for 12.45% of the burden of diseases in Ethiopia and 12% of the Ethiopian people are suffering from some form of mental health problems of which 2% are severe cases. Therefore, the present study was an attempt to investigate the knowledge, attitude and willingness to interact with mentally ill people among inschool adolescents in the four Wollega zones. To this effect, the study attempted to provide answers for the following three research questions.

What is the level of knowledge of the adolescents regarding mental illness?

What is the attitude of adolescents towards mental illness and mentally ill people?

To what extent do the adolescents willing to interact with a person with a mental illness?

Research design

The present study is a cross-sectional survey design, which enabled the researchers to determine adolescents’ knowledge, attitude and willingness to interact with people with mental illness.

Study site

This study was conducted on some selected secondary and preparatory schools in the four Wollega zonal towns (Dembi Dollo, Gimbi, Nekemte, and Shambu).

Population and sampling techniques

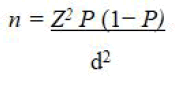

The population of this study was in-school adolescents who were in secondary and preparatory schools in the four Wollega zonal towns in the year 2019. From each four Wollega Zonal towns, two schools (one secondary and one preparatory) were randomly selected; hence, 4 secondary and 4 preparatory schools were included in the study. The total population of secondary and preparatory school students was obtained from the record offices. Accordingly, 16,347 students were enrolled in Kelem Secondary, Kelem Preparatory, Shambo Secondary, Shambo Preparatory, Gimbi Secondary, Gimbi Preparatory, Dalo Secondary and Nekemte Preparatory schools. Sample size for this study was decided with the following formula used for behavioral science studies.

Where,

n=sample size,

Z=Z statistic for a level of confidence of 95% (1.96.),

P=expected prevalence or proportion (in proportion of one; if 50%, P=0.5), and d=precision (in proportion of one; if 5%, d=0.05).

Accordingly, the calculated sample size for the desired precision was 384. The total number of students that took part in this study from each school was determined using proportional method. Moreover, although 384 participants filled and returned the questionnaire, at the time of data encoding the responses of 25 participants have been identified as incomplete; consequently, they have not been included in the analysis. Therefore, the analysis and interpretation of the data was performed on responses from 359 participants. To deal with this, students’ population and samples drawn were summarized according to the following Table 1.

| School | Population | Expected Sample Size | Actual Sample Size |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kelem Secondary | 2400 | 56 | 53 |

| Kelem Preparatory | 1700 | 40 | 35 |

| Shambo Secondary | 2058 | 48 | 48 |

| Shambo Preparatory | 1194 | 28 | 28 |

| Gimbi Secondary | 2267 | 54 | 51 |

| Gimbi Preparatory | 3030 | 71 | 67 |

| Dalo Secondary | 1190 | 28 | 27 |

| Nekemte Preparatory | 2508 | 59 | 50 |

| Total | 16347 | 384 | 359 |

Table 1: Secondary and preparatory school students' population and samples in 2019.

Instruments of data collection

The survey consisted of three measures constructed to assess adolescents’ knowledge, attitude, and willingness to interact with people with mental illness. The instruments were adapted from. The knowledge measure consists of 17 factual statements about mental illness which were rated on a 3-point Likert scale, from Disagree to Agree. The attitude measure also consists of 17 opinion statements which were rated on the same 3-point Likert scale. Reverse items were included in each scale such that correct knowledge or positive attitudes would be reflected by disagreement with the statement. The third major instrument is a social distance scale i n which respondents were indicated their degree of willingness to interact with people with mental illness in specific social situations. The social distance scale consists of 8 items which were rated on a 3-point Likert scale, from Disagree to Agree.

Method of data analysis

After the necessary data were collected and coded, statistical tests were performed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) for Window, version 21.0. Descriptive statistics was used for the analysis of the basic demographics and survey items of the questionnaire.

This chapter has dealt with the results of the data gathered using questionnaire. Descriptive statistics, particularly frequency and percentage were conducted to examine the socio-demographic characteristics, adolescents’ knowledge, attitude, and willingness to interact with people with mental illness.

The background characteristics shown in the Table 2 above were the number of sex wise respondents that participated in the study through questionnaire. Accordingly, 168 (46.8%) were male adolescents and 191 (53.2%) were female adolescents. Age of the respondents was categorized into three: less than 14 years (early adolescents), 14 to 16 years (middle adolescents) and 17 to 19 years (late adolescents). The analysis of the age shows that adolescents with less than 14 year were 1 (0.3%), 14 to 16 years were 201 (56%) and 17 to 19 years were 157 (43.7%). With regard to religion, 264 (73.5%) belongs to Protestant, while 80 (22.3 %) and 10 (2.8 %) of the participants reported they were followers of Orthodox Christianity and Muslim religions, respectively. The remaining 5 (1.4%) reported that they were followers of other religions.

| Background Characteristics | N | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Male | 168 | 46.8 |

| Female | 191 | 53.2 | |

| Age | <14 years | 1 | .3 |

| 14-16 years | 201 | 56.0 | |

| 17-19 years | 157 | 43.7 | |

| Religion | Orthodox | 80 | 22.3 |

| Protestant | 264 | 73.5 | |

| Muslim | 10 | 2.8 | |

| Others | 5 | 1.4 | |

Table 2: Numbers and percentages of adolescents in terms of background characteristics.

Adolescents' knowledge about mental illness

In response to the knowledge of adolescents about mental illness, quantitative data analysis was conducted. The quantitative data were computed through descriptive statistical tools, mainly using frequency and percentage. Seventeen items were set for this purpose and summarized in Table 3 below.

| No | Item | Rating Scale | F | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | “Psycho and maniac” are okay terms for mental illness | Disagree | 159 | 44.3 |

| Undecided | 57 | 15.9 | ||

| Agree | 143 | 39.8 | ||

| 2 | People with mental illness are hurt by slang names for their disorders | Disagree | 108 | 30.1 |

| Undecided | 61 | 17.0 | ||

| Agree | 190 | 52.9 | ||

| 3 | Mental illness is not a very serious problem |

Disagree | 62 | 17.3 |

| Undecided | 48 | 13.4 | ||

| Agree | 249 | 69.4 | ||

| 4 | Parents are usually to blame for a child’s mental illness | Disagree | 141 | 39.3 |

| Undecided | 65 | 18.1 | ||

| Agree | 153 | 42.6 | ||

| 5 | People with mental illness are often treated unfairly | Disagree | 116 | 32.3 |

| Undecided | 70 | 19.5 | ||

| Agree | 173 | 48.2 | ||

| 6 | Mental illness is often shown in negative ways on TV and in movies | Disagree | 123 | 34.3 |

| Undecided | 88 | 24.5 | ||

| Agree | 148 | 41.2 | ||

| 7 | Psychological treatment (such as talking to a psychologist or counselor) is useful | Disagree | 59 | 16.4 |

| Undecided | 41 | 11.4 | ||

| Agree | 259 | 72.1 | ||

| 8 | People with mental illness tend to be violent and dangerous | Disagree | 184 | 51.3 |

| Undecided | 72 | 20.1 | ||

| Agree | 103 | 28.7 | ||

| 9 | People with mental illness are more likely to lie | Disagree | 137 | 38.2 |

| Undecided | 98 | 27.3 | ||

| Agree | 124 | 34.5 | ||

| 10 | People who have had mental illness include astronauts, presidents, and famous baseball players | Disagree | 102 | 28.4 |

| Undecided | 83 | 23.1 | ||

| Agree | 174 | 48.5 | ||

| 11 | Mental illness is often confused with the effects of drug abuse | Disagree | 123 | 34.3 |

| Undecided | 80 | 22.3 | ||

| Agree | 156 | 43.5 | ||

| 12 | Mental illness is caused by something biological | Disagree | 178 | 49.6 |

| Undecided | 88 | 24.5 | ||

| Agree | 93 | 25.9 | ||

| 13 | Giving medicine is a useful way to treat mental illness | Disagree | 75 | 20.9 |

| Undecided | 55 | 15.3 | ||

| Agree | 229 | 63.8 | ||

| 14 | Mental illness and mental retardation are the same thing | Disagree | 84 | 23.4 |

| Undecided | 133 | 37.0 | ||

| Agree | 142 | 39.6 | ||

| 15 | A person with bipolar (manic-depressive) disorder acts overly energetic | Disagree | 128 | 35.7 |

| Undecided | 109 | 30.4 | ||

| Agree | 122 | 34.0 | ||

| 16 | Most people with severe forms of mental illness do not get better, even with treatment | Disagree | 112 | 31.2 |

| Undecided | 105 | 29.2 | ||

| Agree | 142 | 39.6 | ||

| 17 | Schizophrenia involves multiple personalities | Disagree | 97 | 27.0 |

| Undecided | 131 | 36.5 | ||

| Agree | 131 | 36.5 |

Table 3: Knowledge of the adolescents regarding mental illness.

Table 3 above indicates that majority, 159 (44.3%), of the adolescents disagreed with the idea “psycho and maniac” are okay terms for mental illness. A considerable number, 143 (39.8%), of the respondents contrasted the above idea, and a few, 57 (15.9%) of them could not decide what to say. In response to item 2 in the same table, almost half, 190 (52.9%), and 108 (30.1%) and 61 (17%) of the respondents agreed, disagreed and undecided to say people with mental illness are hurt by slang names for their disorders.

With regard to item 3 in Table 3, high proportion, 249 (69.4%), of the respondents agreed that mental illness is not a very serious problem. Sixty two (17.3%) and 48 (13.4%), of the respondents respectively confirmed that they disagreed and undecided to the item. Regarding item 4 in Table 3, 153 (42.6%) of the respondents agreed that parents are usually to blame for a child’s mental illness, yet 141 (39.3%) and 65 (18.1%) of the respondents respectively disagreed and uncertain to the item.

In item 5 in Table 3, a great number of respondents, 173 (48.2%) reported that people with mental illness are often treated unfairly. Hundred sixteen (32.3%) of them disagreed and 70 (19.5%) were uncertain. In item 6, 148 (41.2%) of the respondents agreed that mental illness is often shown in negative ways on media, 123 (34.3%) and 88 (24.5%) of them respectively disagree and undecided to the item.

In response to item 7 in Table 3 above, high proportion, 259 (72.1%), of the respondents agreed that psychological treatment (such as talking to a psychologist or counselor) is useful for people with mental illness. Fifty nine (16.4%) and 41 (11.4%), of the respondents respectively confirmed that they disagreed and undecided to the item. Regarding item 8, about half, 184 (51.3%), 103 (28.7%) and 72 (20.1%) of the respondents disagreed, agreed and undecided to say people with mental illness tend to be violent and dangerous. In item 9, 137 (38.2%) of the respondents disagree that people with mental illness are more likely to lie, 124 (34.5%) and (9810.6%) of them respectively agreed and uncertain to the item.

The respondents continued saying that people with mental illness can achieve successes in different professions. For example, 174 (48.5%) of them agreed that people who have had mental illness include astronauts, presidents, and famous baseball players, yet 102 (28.4%) and 83 (23.1%) of the respondents respectively disagreed and uncertain to the item. In item 11, a great number of respondents, 156 (43.5%) reported that mental illness is often confused with the effects of drug abuse. Hundred twenty three (34.3%) of them disagreed and 80 (22.3%) were uncertain.

With regard to item 12 in Table 3, almost half, 178 (49.6%) disagreed that mental illness is caused by something biological. Almost quarters, 93 (25.9%) and 88 (24.5%) of the adolescents were agreed and uncertain whether mental illness is caused by something biological or not, respectively. In item 13, majority of the respondents, 229 (63.8%) agreed with the idea giving medicine is a useful way to treat mental illness, but 75 (20.9%) disagreed and 55 (15.3%) of them could not decide.

In item 14, Table 3 above, the respondents were required to tell whether mental illness and mental retardation are the same thing or different. Accordingly, 142 (39.6%) of the respondents agreed that mental illness and mental retardation are the same thing. Hundred thirty three (37%) and 84 (23.4%) of them respectively reported that they are not the same thing and are uncertain of it. In item 15, 128 (35.7%) of the respondents disagree with the idea that a person with bipolar (manicdepressive) disorder acts overly energetic. Hundred twenty two (34%) and 109 (30.4%) of them respectively reported that a person with bipolar disorder does not act overly energetic and are uncertain of it.

In response to item 16 in Table 3 above, high proportion, 142 (39.6%) of the respondents agreed that most people with severe forms of mental illness do not get better, even with treatment. Hundred twelve (31.2%) and 105 (29.2%) of the respondents respectively confirmed that they disagreed and undecided to the item. In item 17, equal number of respondents, 131 (36.5%) each agreed and not certain regarding the statement stating schizophrenia involves multiple personalities, while almost a quarter, 97 (27%) of the respondents disagree with the idea.

Adolescents’ attitude towards mental illness and mentally ill people

To investigate adolescents’ attitude towards mental illness and mentally ill people, quantitative data were analyzed and described using descriptive statistics, particularly frequency and percentage. Seventeen items were set for this purpose and summarized in Table 4 below.

| No | Item | Rating Scale | F | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | People with mental illness deserve respect | Disagree | 32 | 8.9 |

| Undecided | 19 | 5.3 | ||

| Agree | 308 | 85.8 | ||

| 2 | We should do more to help people with mental illness get better | Disagree | 27 | 7.5 |

| Undecided | 21 | 5.8 | ||

| Agree | 311 | 86.6 | ||

| 3 | Jokes about mental illness are hurtful | Disagree | 85 | 23.7 |

| Undecided | 71 | 19.8 | ||

| Agree | 203 | 56.5 | ||

| 4 | It is important to learn about mental illness | Disagree | 37 | 10.3 |

| Undecided | 36 | 10.0 | ||

| Agree | 286 | 79.7 | ||

| 5 | A person with mental illness is able to be a good friend | Disagree | 127 | 35.4 |

| Undecided | 110 | 30.6 | ||

| Agree | 122 | 34.0 | ||

| 6 | It is a good idea to avoid people who have mental illness | Disagree | 76 | 21.2 |

| Undecided | 60 | 16.7 | ||

| Agree | 223 | 62.1 | ||

| 7 | I would be comfortable meeting a person with a mental illness | Disagree | 99 | 27.6 |

| Undecided | 100 | 27.9 | ||

| Agree | 160 | 44.6 | ||

| 8 | People with mental illness are able to help others |

Disagree | 161 | 44.8 |

| Undecided | 82 | 22.8 | ||

| Agree | 116 | 32.3 | ||

| 9 | I would be frightened if approached by a person with mental illness | Disagree | 125 | 34.8 |

| Undecided | 86 | 24.0 | ||

| Agree | 148 | 41.2 | ||

| 10 | If I had a mental illness, I would not tell any of my friends |

Disagree | 72 | 20.1 |

| Undecided | 64 | 17.8 | ||

| Agree | 223 | 62.1 | ||

| 11 | If any friends of mine had a mental illness, I would tell them not to tell anyone | Disagree | 78 | 21.7 |

| Undecided | 72 | 20.1 | ||

| Agree | 209 | 58.2 | ||

| 12 | Keeping people with mental illness in the hospital makes the community safer | Disagree | 185 | 51.5 |

| Undecided | 59 | 16.4 | ||

| Agree | 115 | 32.0 | ||

| 13 | Only people who are weak and overly sensitive let mental illness affect them | Disagree | 52 | 14.5 |

| Undecided | 85 | 23.7 | ||

| Agree | 222 | 61.8 | ||

| 14 | It would be embarrassing to have a mental illness | Disagree | 52 | 14.5 |

| Undecided | 59 | 16.4 | ||

| Agree | 248 | 69.1 | ||

| 15 | Students with mental illness shouldn’t be in regular classes |

Disagree | 111 | 30.9 |

| Undecided | 79 | 22.0 | ||

| Agree | 169 | 47.1 | ||

| 16 | I have little in common with people who have mental illness | Disagree | 84 | 23.4 |

| Undecided | 109 | 30.4 | ||

| Agree | 166 | 46.2 | ||

| 17 | Students with mental illness need special programs to learn | Disagree | 220 | 61.3 |

| Undecided | 69 | 19.2 | ||

| Agree | 70 | 19.5 |

Table 4: Attitude of adolescents towards mental illness and mentally ill people.

Table 4 above has shown an analysis of adolescents’ attitude towards mental illness and mentally ill people. Regarding the first item, the majority of the adolescents, 308 (85.8%) agreed with the idea that people with mental illness deserve respect. However, 32 (8.9%) of the respondents responded that they didn’t agree with the statement. The rest, 19 (5.3%) of the respondents could not decide what to say. With regard to Item 2 of the same table, majority, 311 (86.6%) of the respondents have shown their willingness to help people with mental illness get better, whereas 21 (5.8%) of them could not decide. The rest 27 (7.5%) of the adolescents were not willing to help people with mental illness.

With item 3, that is jokes about mental illness are hurtful, 203 (56.5%) of the respondents agreed with the idea. Eight five (23.7%) of them disagreed to the issue, whereas 71 (19.8%) of them marked undecided. With regard to item 4 of Table 4, the importance of learning about mental illness, greater proportion, 286 (79.7%) of the respondents have sown their willingness to learn about mental illness. Thirty-seven (10.3%) adolescents responded that they did not find it is useful to learn about mental illness. The remaining 36 (10%) of them replied undecided.

Concerning item 5 of Table 4, 127 (35.4%) of the respondents disagreed with the idea that a person with mental illness is able to a good friend, whereas 122 (34%) and 110 (30.6%) of them agreed and unsure to decide, respectively. With regard to item 6 in Table 4, that is whether it is a good idea to avoid people who have mental illness, 223 (62.1%) of the respondents agreed with the idea. In contrast, 76 (21.2%) responded disagree whereas the rest 60 (16.7%) of them were unsure of what to do, respectively.

Of item 7 in Table 4, that is feeling comfortable meeting a person with mental illness, 160 (44.6%) of the respondents agreed; 99 (27.6%) of them did not show their willingness of meeting a person with a mental illness, and 100 (27.9%) of the adolescents chosen the option undecided. item 8 of the same table, which is about whether people with mental illness are able to help others, 161 (44.8%) of the respondents disagreed to the idea. On the other hand, 116 (32.3%) of the respondents agreed, that is, they believe that people with mental illness are able to help others. The remaining 82 (22.8%) of the respondents revealed that they could not decide.

With regard to item 9 in Table 4, 148 (41.2%) of the respondents agreed with the idea that they are being frightened if approached by a person with mental illness, whereas 125 (34%) and 86 (24%) of them disagreed and unsure to decide, respectively. Regarding to item 10 of the same table, the majority of adolescents, 223 (62.1%) reported that they would not tell to their friends if they had mental illness, whereas 72 (20.1%) of them did not agree with the idea. The rest 64 (17.8%) of the adolescents were not sure whether to tell to their friends or not. In relation to item 11, 209 (58.2%) of the respondents revealed that they suggest their friends not to tell to any one if they had mental illness, whereas 78 (21.7%) and 72 (20.1%) of them disagreed with the idea and unsure what to do, respectively.

In item 12, Table 4 above, the respondents were required to tell their perceptions whether keeping people with mental illness in the hospital make the community safer or not. Almost half, 185 (51.5%) of the respondents disagreed with the opinion, while 115 (32%) and 59 (16.4%) of them respectively reported that keeping people with mental illness in the hospital makes the community safer and are uncertain of it. In response to item 13, the majority of adolescents, 222 (61.8%) perceived that weak and overly sensitive people are being affected by mental illness, whereas 85 (23.7%) and 52 (14.5%) of them respectively marked undecided and disagree to the idea.

With regard to items 14 and 15, majority of the respondents explained that experiencing mental illness is something difficult and does not allow attending regular classes. For example, in item 14, 248 (69.1%) of them perceived that it would be embarrassing to have a mental illness. A few of them, 52 (14.5%) and 59 (16.4%) respectively responded that experiencing mental illness is not something embarrassing and were uncertain to say what. In item 15, 169 (47.1%) agreed that students with mental illness shouldn’t be in regular classes, but 111(30.9%) disagreed and 79 (22%) of them could not decide.

In items 16 and 17, Table 4 above, the respondents were required to tell their attitude whether they want to deal with mentally ill people and students with mental illness need special programs to learn or not. In item 16, 166 (46.2%) of the respondents agreed that they have little in common with people who have mental illness. Eighty-four (23.4%) and 109 (30.4%) of them respectively reported that they disagree with the idea and are uncertain of it. On the other hand, in item 17, the majority of the respondents, 220 (61.3%) disagree that students with mental illness need special programs to learn. Seventy (19.5%) and 69 (19.2%) of them respectively reported that students with mental illness do not need special programs to learn and are uncertain of it.

Adolescents’ willingness to interact with a person with mental illness

To investigate adolescents’ willingness to interact with people with mental illness, the researchers analyzed data gathered through questionnaire using descriptive statistics, mainly, frequency and percentage. Eight items were set for this purpose and summarized in Table 5 below.

| No | Item | Rating Scale | F | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Talk to someone with a mental illness | Disagree | 87 | 24.2 |

| Undecided | 51 | 14.2 | ||

| Agree | 221 | 61.6 | ||

| 2 | Make friends with someone with a mental illness | Disagree | 141 | 39.3 |

| Undecided | 80 | 22.3 | ||

| Agree | 138 | 38.4 | ||

| 3 | Have someone with a mental illness as a neighbor | Disagree | 92 | 25.6 |

| Undecided | 101 | 28.1 | ||

| Agree | 166 | 46.2 | ||

| 4 | Have someone with a mental illness in a class with you | Disagree | 107 | 29.8 |

| Undecided | 94 | 26.2 | ||

| Agree | 158 | 44.0 | ||

| 5 | Sit next to someone with a mental illness | Disagree | 111 | 30.9 |

| Undecided | 86 | 24.0 | ||

| Agree | 162 | 45.1 | ||

| 6 | Invite someone with a mental illness to your home | Disagree | 118 | 32.9 |

| Undecided | 64 | 17.8 | ||

| Agree | 177 | 49.3 | ||

| 7 | Work on a class project with someone with mental illness |

Disagree | 119 | 33.1 |

| Undecided | 85 | 23.7 | ||

| Agree | 155 | 43.2 | ||

| 8 | Go on a date with someone with a mental illness | Disagree | 170 | 47.4 |

| Undecided | 91 | 25.3 | ||

| Agree | 98 | 27.3 |

Table 5: Adolescents’ willingness to interact with a person with mental illness.

Table 5 presents willingness to talk to someone with a mental illness. The result of the analysis revealed, the majority of the respondents, 221 (61.6%) agreed that they have willingness to talk to someone with a mental illness. However, 87 (24.2%) of the respondents did not agree with the idea. Meanwhile, 51 (14.2%) of the respondents lied on the intermediate scale, undecided. item 2 of the same table is concerned with adolescents' willingness to establish friendship with someone with a mental illness. The result shows that 141 (39.3%) respondents disagreed to the idea. Unlike this, 138 (38.4%) of the respondents agreed that they want to make friends with someone with a mental illness, whereas the least, 80 (22.3%) of them marked undecided.

Items 3 and 4 in Table 5 investigated whether adolescents have someone with a mental illness as a neighbor and in class. Accordingly, 166 (46.2%) of the respondents replied that they have someone with a mental illness as a neighbor, while 92 (25.6%) and 101 (28.1%) of the respondents reported that they didn’t have someone with mental illness in their neighborhood and could not decide, respectively. The result of item 4 indicates that 158 (44%) of the respondents agreed that they are willing to have someone with a mental illness in a class with them. Hundredseven (29.8%) of the respondents did not agree with the idea, while 94 (26.2%) were uncertain.

Item 5 of Table 5 explored adolescents’ willingness to sit next to someone with a mental illness. Accordingly, 162 (45.1%) of the respondents revealed that they have willingness to sit next to someone with a mental illness. Unlike this, 111 (30.9%) of the respondents disagreed the issue of sitting next to someone with a mental illness. The other 86 (24%) respondents reply was undecided.

The sixth item of the same table looked into adolescents’ willingness to invite someone with a mental illness to their home. As the consequence of the analyzed data, 177 (49.3%) of the adolescents showed their agreement with the idea. Hundredeighteen (32.9%), among the participant adolescents of the study did not agree with the idea of inviting someone with a mental illness to their home. The rest of the respondents, 64 (17.8%) chosen the undecided option.

Willingness to work on a class project with someone with mental illness was dealt with on Item 7 of Table 5. The analyzed result depicts that 155 (43.2%) agreed, 119 (33.1.1%) disagreed and 85 (23.7%) undecided. The last item of Table 5 is whether adolescents were willing to go on a date with someone with mental illness. The result of the analysis shows that 170 (47.4%) of the adolescents did not show their willingness to go for dating with someone with mental illness. On the other hand, 98 (27.3%) of them have shown their willingness. Still, almost a quarter, 91 (25.3%) of the respondents could not decide what to do.

The results revealed that secondary and preparatory school adolescents’ knowledge of mental illness is inconsistent. They were with better knowledge regarding the inappropriate treatment and representation of people with mental illnesses. This finding is consistent with, who reported that middle school students were wellinformed about the unfavorable treatment and depiction of people with mental illnesses. However, their knowledge is seemingly poor in some other areas. For instance, most respondents viewed mental illness as not a very serious problem. This result is contradicting with finding, who argue that mental illness is serious problem disrupting a person’s thinking, feeling, experience, emotions, mood, ability to relate to other and daily functioning or causing functional impairment in people, making it more difficult for them to sustain interpersonal relationships and carry on their jobs, and sometimes leading to self- destructive behaviors and even suicide.

Congruent with, the present finding revealed that the majority of adolescents did not know that overly energetic behavior is a characteristic of bipolar disorder or that mental illness and mental retardation are not the same.

Another unexpected result was adolescents’ responses to the knowledge items involving the biological aspects of mental illness and its treatments. Given mental illness is conceptualized as having biological roots and drugs are useful to treat variety of psychiatric conditions, it was expected that the adolescents would view mental illness primarily as a biological condition and identify drugs as a main treatment. However, consistent with finding, the result of this study revealed about half adolescents (49.6%) expressed their disagreement regarding mental illness had a biological cause and less than half (39.6%) agreed that medicine is useful in the treatment of mental illness.

One more unanticipated result involved fears of violence. A major component of adult views of mental illness is the inaccurate belief that those with psychiatric disorders tend to be violent and dangerous. It was expected that this belief would be shared by adolescents as well. However, congruent with the present study finding revealed that only 28.7%secondary and preparatory school adolescents agreed that people with mental illness tend to be violent and dangerous, and a far greater percentage (51.3%) disagreed.

Lastly, with respect to knowledge of mental illness, it appears that the adolescents were not optimistic about the potential for recovery of people with severe mental illnesses. Almost two in three thought such individuals would not benefit from treatment. The more optimistic expectations of the recovery movement have apparently not been incorporated into the understanding of adolescents, raising the concern that the unwarranted pessimism about the treatment and recovery of persons with severe mental illness of earlier generations continues to be felt.

As noted from the result, adolescents’ attitudes towards people with mental illness were mixed; given that some of the adolescents expressed accepting, respectful, and sympathetic views toward people with mental illness, still large proportion of the adolescents were fearful of approaching and to be a friend of mentally ill person. These results are a hopeful sign that the next generation may be developing more positive attitude toward mental illness than those of older generations. However, still considerable number of adolescents indicated negative attitude toward people with mental illness are still potentially problematic. The majority (61.8%) of adolescents agreed that only individuals who are weak and overly sensitive let themselves be affected by mental illness and almost the same percentage (62.1) reported that they would not tell any of their friends, if they had a mental illness. Similarly, the majority (69.1) of adolescents reported that they would find it embarrassing to have a mental illness. Nearly half (46.2%) saw themselves as having little in common with a person with mental illness and about the same percentage (44.8%) indicated that people with mental illness are not able to help others. The result of this study supports most previous research findings. For instance, argue that persons labelled as mentally ill are perceived with attributes that are more negative and are more likely to be rejected regardless of their behaviour. Stigma remains a powerful negative attribute in all social relations. Also reported that people who are labelled as mentally ill associates themselves with society’s negative conceptions of mental illness and that society’s negative reactions contribute to the incidence of mental disorder. The social rejection resulting from this may handicap mentally ill people even further.

Results of willingness to interact with people with mental illness revealed positive attitude by majority of respondents and less accepting views by a few of the respondents. For example, only 39.3% of the adolescents indicated unwillingness to make friends with someone with mental illness, and only 47.4% expressed lack of willingness to go on a date with someone with a mental illness. The results also mirrored a frequent finding by studies that measure social distance: the more intimate the relationship, the less willing is an individual to interact with someone with a mental illness. Although 61.6% of adolescents were willing to talk to someone with a mental illness, only 49.3% were willing to sit next to such a person, and a mere 27.3% would consider dating that person. Such results imply that people with mental illness still experiences substantial rejection and exclusion by their peers.

The findings of the study concerning the knowledge, attitude and willingness to interact with mentally ill people among in-school adolescents in the four Wollega zones, performed using descriptive approach, were concluded for the three basic research questions. Accordingly, the results revealed that in-school adolescents’ knowledge of mental illness is inconsistent. They were informed well about the inappropriate treatment and representation of people with mental illnesses. However, their knowledge is poor in other areas. For instance, most respondents viewed mental illness as not a very serious problem.

Attitudes expressed toward mentally ill people among these adolescents were mixed; some of the adolescents expressed accepting, respectful, and sympathetic views toward people with mental illness. Still large proportions of the respondents were fearful of approaching and to be a friend of mentally ill person. Social distance results revealed positive attitude by majority of respondents and less accepting views by a few of them. It is therefore recommended that the four Wollega Zonal town health offices need to educate adolescents regarding specific disorders and about acceptance of individuals with mental illness.

Citation: Derra GT, et al. "Knowledge, Attitude and Willingness to Interact with Mentally Ill People among In- School Adolescents in the Four Wollega Zones". Prim Health Care, 2022, 12(4), 1-10.

Received: 21-Apr-2022, Manuscript No. JPHC-22-61425; Editor assigned: 23-Apr-2022, Pre QC No. JPHC-22-61425(PQ); Reviewed: 09-May-2022, QC No. JPHC-22-61425; Revised: 21-Jun-2022, Manuscript No. JPHC-22-61425(R); Published: 28-Jun-2022, DOI: DOI: 10.4172/2167-1079.22.12.6.1000446

Copyright: © 2022 Derra GT, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.