Research Article - (2021) Volume 11, Issue 4

Background: Contraception is a worthwhile and cost effective investment that has potential to spur national development. It is important in averting significant maternal and childhood morbidity and mortality. No wonder countries with low contraceptive prevalence rates (CPR) have poor maternal and childhood health indicators. Consequently, during the 2012 London conference Uganda set a target of improving modern CPR (mCPR) to 50% by 2020. We report how eastern Uganda is faring on this commitment and identify the factors associated with contraceptive uptake.

Methods: Using a cross-sectional study design, we recruited 418 sexually active women aged 15-49 years who had come to nurse their sick ones in a tertiary hospital. We used systematic sampling to recruit participants. Data was collected using an interviewer administered pretested questionnaire, analyzed using STAT version 19.

Results: Of the 418 women respondents, 15.6% were teens while 50% were aged 20-29 years. Significantly, 64.59% were married. The majority, 78.7% were informally employed, and more than 62% were Christians. Moreover, 97.8% were formal educated and 52.2% had 1-4 living children. The overall contraceptive prevalence was 33.7% while mCPR was 30.86%. Significantly whereas 36.6% had ever used contraception, 29.7% had never. The top contraceptives choices were injectables (56.7%), implants (27%), calendar method (6.4%) and abstinence (2.8%). Significantly, 99.8% were aware of contraception and, radio (91%) and health workers (82%) being major sources of information. Significant factors affecting uptake include age and marital status, youngest child’s age, decision when to have next child, history of sexually transmitted disease, partner’s age and support.

Conclusion: The contraceptive prevalence rates are below the national average and the London target despite significant awareness among women. Efforts to increase uptake should include male involvement, continued dissemination of information and reinforcing sexual and reproductive health education in schools. This will help to demystify misconceptions, misapprehensions and myths about contraceptives.

Contraception • London 2012 summit • Male support • Uganda

Contraceptive use permits women in reproductive age to reach their desired number of children, plan the intervals between pregnancies and avert morbidity and mortality. Contraception is the intentional prevention of pregnancy as a result of sexual intercourse through use of artificial or modern methods and the Natural or Traditional methods. Furthermore, the prevalence of contraceptive use is defined as “the percent of women of reproductive age who are utilizing (or whose sexual partner is utilizing) a contraceptive method at any particular point of time, almost always calculated for married women” [1].

Among the 1.9 billion Women of Reproductive Age group (WRAG) 15-49 years, worldwide in 2019, 57.9% (1.1 billion) had a need for family planning yet only 44.3%( 842 million) were using contraceptive methods . It was also ascertained that 270 million have an unmet need for contraception [2] yet contraceptive use has been associated with benefits to mother, child and family at large [3].

Embracing contraceptive uptake has been associated with significant reduction in maternal and perinatal morbidity and mortality. For example, marked increase in uptake in the Western world reduced percentage of unintended pregnancies and the reduction of maternal mortality by 40% [3]. The benefits of increased prevalence of contraception have been demonstrated in both developed and developing countries [3]. Therefore investing and embracing modern contraception would be a very cost effective route to attainment of sustainable development goals 1, 2, 3,4 and 5 [4].

However, despite increase in contraceptive use in many parts of the world such as at 61.8% in Asia and 66.7% in Latin America, it is still low in SSA at only 28.5% [5] yet the later contributes to 68% of the global maternal mortality ratio [6]. Moreover, countries with the low contraceptive uptake have poor maternal and child health indicators compared to those with a higher contraceptive uptake. For example United States of America (USA)with Contraceptive Prevalence Rate (CPR) of 76.4%, has a maternal mortality ratio (MMR), CPR of 59.9% for South Africa with MMR of 119, Niger with lower CPR at 13.9%, and MMR of 509 per 100,00O live births Moreover, several data from other African countries show similar trends of lower CPR and higher MMR. For example Uganda CPR at 27.2%, FR of 5.71 MMR of 336, high FR of 6.49, high MMR. Therefore investing in contraception is a need especially for SSA countries like Uganda.

In 2012, a watershed summit built on 50 years of dedicated work by the global reproductive health sector to bring contraception within reach of every woman around the world was held in London. In this summit, several countries including Uganda made commitments to ensuring that availability of contraception to every woman that needs it. A commitment to ensure that an additional 120 million women use modern contraceptive methods by 2020 in the world’s 69 poorest countries was observed and that to achieve this, the total pre-2012 annual growth rate of modern contraceptive prevalence rates would have to be doubled from the then 0.7 to 1.4 percentage points.

Uganda committed to ensuring that unmet need for family planning reduces from 28% to 10%, and modern contraceptive prevalence rate reaches 50% by 2020. In a bid to meet these ambitions, the Uganda government scaled up investment and even introduced youth-friendly family planning services to 50% of the government’s Level IV Health Centers and 100% of district hospitals.

However, Uganda still grapples with high rates of unintended teenage pregnancies that continue to wreckhavoc in the livelihoods of teenage girls [7], high maternal mortality ratio of 336 per 100,000 live births and neonatal mortality rate (NMR)of 27/1000 live births(Uganda Bureau of Statistics Kampala, 2017) . Moreover, Uganda has a high NMR of 27 per 1000 live births. The NMR of 34/1000 live births in Eastern Uganda [8] is a higher than the national average. These indicators threaten the attainment of SDG targets 3.1 and 3.2. These aim to reduce global MMR to less than 70 per 100 000 live births and preventable deaths of newborns and children under 5 years of age, to as low as 12 per 1,000 live births and under-5 mortality to at least as low as 25 per 1,000 live births. We therefore aimed at studying how eastern Uganda, one of the regions with poor health indicators (such as higher than national averages of teenage pregnancy and NMR) was faring as far as the commitment is concerned and the associated factors.

Research design, study area and study population

This was a cross sectional descriptive study from carried out from March to August 2020 from Mbale Regional Referral hospital. The hospital located in Mbale district, eastern Uganda serves as a regional referral hospital for 16 districts in the eastern region. It is also a teaching hospital for Busitema University and serves as a national internship-training site. It is a 400 beds capacity hospital with several departments, which include Paediatrics and Child Health, Surgery, Obstetrics and Gynaecology and Medicine. The hospital serves over 4 million people within the catchment area of about 15 districts. In this hospital, each patient has their own attendant or attendants and these are largely females.

The study population was all sexually active fecund, non-pregnant women of reproductive age (WRAG) 15-49 years who were residents of eastern Uganda.

Sampling method

We used systematic random sampling technique.

Sample size estimation

We used Kish Leslie formula (1965) for cross sectional studies.

Given

Where; N=Sample size estimate Z= confidence level at 95 % (standard value of 1.96). P= Contraceptive prevalence, Q= (1-P) and d= Acceptable margin of error at 5% or 0.05. We used the study in Northern part of Uganda in which the researchers reported a contraceptive rate of 44.6% [9]. The calculated sample size N= [1.96²×0.446× 0.554/0.052]=380

Taking a non-responsive rate of 10%, the minimum number of the study subjects N0 was

Study variables

Contraceptive prevalence rate (CPR) is the dependent variable and the Independent variable were the factors associated with contraceptive uptake.

Data collection method and management

A face-to-face interviewer administered pretested questionnaire was used was used to collect data relevant to the objectives of the study. The questionnaire was pretested on 05 women attending to patients admitted in Mbale Regional Referral Hospital before data collection to assess for reliability and validity of questionnaire. This questionnaire was prepared for this study (supplement).

We checked all questionnaires were for completeness, double entered and cleaned using Microsoft excels and imported it to Stata version 19 for analysis. Using frequency distribution and two-way tables, we summarise the data. We used chi-square for P-value derivation for factors that were significantly associated with contraceptive uptake. We considered variables with p value ≤ 0.05 in bivariate logistic regression for multivariate logistic regression. At multivariate analysis, we took factors with P - value < 0.05 as statistically significant with 95% confidence interval.

Demographic characteristics

A total number of 418 sexually active women of reproductive age (WRAG) 15-49 years participated in this study. The mean age was 27.35 (SD 7.79) with the major age group being that of the 20-24 year olds. Slightly over a half of them, 51.9% (217/418) were rural residents while, 48.1% (201/418) were urban residents. Significantly the majority, 97.8% had had formal education with 69.6% accessing at least secondary education.

Moreover, the majority 64.6% (270/418) was married while about 35.4% were not married with the mean marriage years of 6.37 (SD 7.89). Concerning religion, majority were Christians with the protestants at 33.5 %( 140/418) while catholics were 28.47%. The majority, 78.7% (329/418) were informally employed while only 21.3% (89/418) were in the formal sector. Of the 64.6% that were married, 43.3% had been married for less than 10 years (Table 1).

| Characteristic | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Age of women, Mean ± SD (n) | 27.35±7.79 |

| 15-19 | 65(15.55) |

| 20-24 | 115(27.51) |

| 25-29 | 96(22.97) |

| 30-34 | 56(13.40) |

| 35+ | 86(20.57) |

| Residence | |

| Rural | 217(51.91) |

| Urban | 201(48.09) |

| Education level | |

| Primary | 118(28.2) |

| Secondary | 197(47.1) |

| Tertiary | 94(22.5) |

| Informal | 9(2.2) |

| Marital status | |

| Married | 270(64.59) |

| Single | 130(31.10) |

| Divorced | 13(3.11) |

| Widowed | 5(1.20) |

| Duration of marriage(years), Mean ±SD (n) | 6.37±7.89 |

| <10 | 181(43.30) |

| >10 | 89(21.29) |

| Not married | 148(35.40) |

| Stays with partner | |

| Yes | 262(62.68) |

| No | 156(37.32) |

| Drink alcohol | |

| Yes | 16(3.83) |

| No | 402(96.17) |

| Employment status | |

| Formal | 89(21.29) |

| Informal | 329(78.71) |

| Tribe | |

| Gishu | 241(57.66) |

| Bagwere | 53(12.68) |

| Banyole | 21(5.02) |

| Itesot | 35(8.37) |

| Others(Basoga,Baganda,Japadhola) | 68(16.37) |

| Religion | |

| Protestant | 140(33.49) |

| Catholic | 119(28.47) |

| Moslem | 90(21.53) |

| Others(Pentecostal, Isamasiya,SDAs) | 69(16.51) |

| Total | 418 |

Table 1: Socio-demographic characteristics of women of reproductive age (15-19) years in Mbale, Eastern Uganda.

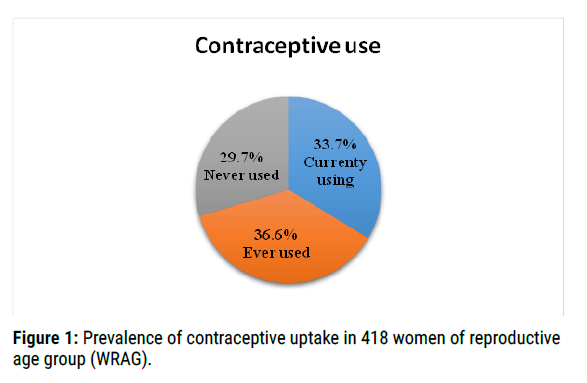

Prevalence of contraceptive uptake

In this study, the prevalence of contraceptive uptake was 33.7% (141/418).Moreover, 36.6% had ever used contraception while 29.7% had never (Figure 1). The majority, 30.6% (128/141) were using modern contraceptives while 3.1 %( 13/141) were using traditional methods.

Figure 1. Prevalence of contraceptive uptake in 418 women of reproductive age group (WRAG).

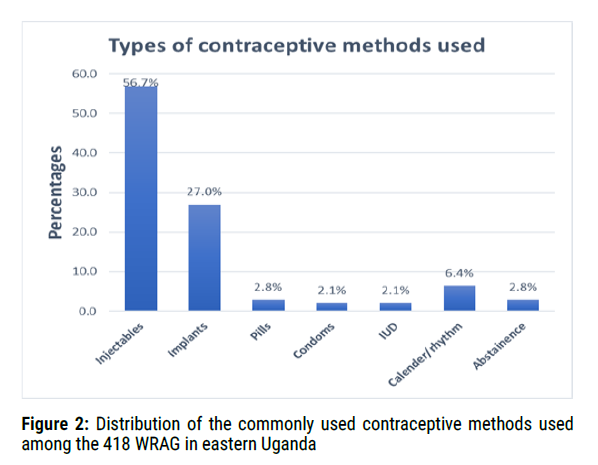

The commonly used modern methods were injectable at 56.7 %( 80/141) followed by the implants at 27% while amongst the traditional methods, the calendar method ranked highest at 6.4% followed by abstinence at 2.4%. (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Distribution of the commonly used contraceptive methods used among the 418 WRAG in eastern Uganda

Factors associated with contraceptive uptake

Several factors influence contraceptive prevalence among WRAG. We therefore sought to study these factors and elucidate their significance in contraceptive use.

Awareness and practice about contraceptives and health system factors

Almost all participants had heard about contraceptives 99.8 %( 417/418) with radio at 90.89% and health workers at 82.49% being the two sources of information. Generally, most participants that had ever used contraceptives had obtained counselling from mainly health workers, 73.2% (306/418). The majority, 57.2% (239/418) believed that contraceptive services were readily available in government health facilities while 36.4% did not know where to get them. Furthermore, the majority of the participants, 73.2 %( 306/418) agreed that health workers were available to give a service and 62.7 %( 262/418) affirmed that the individual’s choice of a contraceptive was always available. Moreover, 63.2 %( 264/418) believed that the points of care were readily accessible. Significantly, half of the respondents stopped contraceptive use due to complications. Not surprising therefore is the fact that 55.3% chose a method because they associated it with fewer side effects while only 7.8% did so because they believed it was safe and reliable (Table 2).

| Characteristics | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Heard about contraceptives | |

| Yes | 417(99.76) |

| No | 1(0.24) |

| Sources of information | |

| Community outreaches | 104(24.94) |

| Friends | 316(75.78) |

| Health worker | 344(82.49) |

| Internet and phone adverts | 43(10.31) |

| Print media | 59(14.15) |

| Radio | 379(90.89) |

| Relatives | 262(62.83) |

| Schools | 147(35.25) |

| Television | 217(52.04) |

| Ever been counseled by | |

| Health worker | 306(73.21) |

| None | 112(26.79) |

| Ever used contraceptives | |

| Yes | 124(29.69) |

| No | 153(36.60) |

| Still using | 141(33.73) |

| Reason for stopping | |

| Wanted to get pregnant | 46(37.10) |

| Had complications | 62(50.00) |

| Advanced age | 16(12.90) |

| Complications | |

| Changes in bleeding patterns | 42(67.74) |

| Low mood | 28(45.16) |

| No menstrual periods | 15(24.19) |

| Pains(Backache, Headache) | 15(24.19) |

| Others(weight gain, Loss of appetite) | 8(12.9) |

| Contraceptive method used | |

| Modern | 128(90.78) |

| Traditional | 13(9.22) |

| Types of contraceptive method used | |

| Injectables | 80(56.74) |

| Implants | 38(26.95) |

| Pills | 4(2.84) |

| Condom | 3(2.13) |

| IUD | 3(2.13) |

| Calendar/rhythm | 9(6.38) |

| Abstinence | 4(2.84) |

| Reason for using | |

| Ease of use | 40(28.37) |

| Less side effects | 78(55.32) |

| Long time use | 42(29.79) |

| No side effects | 50(35.46) |

| Privacy | 22(15.6) |

| Safe and reliable | 11(7.8) |

| Short time use | 75(53.19) |

| Others(no needle pricks, Prevention of STIs) | 8(5.67) |

| Health system factors | |

| Contraceptives access points | |

| Government health facility | 239(57.18) |

| Clinic/Private/hospital | 16 (3.83) |

| Reproductive Health facility & Pharmacy | 9(2.15) |

| Do not know | 154(36.84) |

| Opinion about availability of health worker | |

| Always | 264(63.16) |

| Not sure | 154(36.84) |

| Opinion about availability of preferred contraceptive of choice | |

| Yes | 262(62.68) |

| Not applicable | 3(0.72) |

| Accessibility to points of care | |

| Yes | 264(63.16) |

| Not applicable | 1(0.24) |

Table 2: Awareness and practices affecting contraceptives’ uptake among WRAG in eastern Uganda.

Obstetric and gynaecological history

The mean number of living children was 2.28(SD2.46) with the majority of the participants 52.2% (218/418) having 1-4 children, 35.2 %( 147/418) had age last child less than 2 years. Furthermore, 16.5% (69/418) had a time plan to the next child above 5 years, 60.8% (254/418) had vaginal delivery. The majority, 86.93% of those that had delivered reported to have had no complication at childbirths while 13.07% did. The major mode of delivery by the majority of respondents was vaginal delivery at 90.39% while caesarean route accounted for 9.61 % (Table 3).

| Characteristic | n (%) |

| Number of Living children, Mean ±SD | 2.28±2.46 |

| No child | 137(32.78) |

| 1-4 children | 218(52.15) |

| 5+ | 63(15.07) |

| Age last child | |

| <2years | 147(35.17) |

| 2-5years | 90(21.53) |

| >5 years | 63(15.07) |

| Time plan to next child | |

| 0-1years | 27(6.46) |

| >1-2years | 60(14.35) |

| >2-4 years | 67(16.03) |

| 5 +years | 69(16.51) |

| Mode of Delivery | |

| Vaginal | 254(90.39) |

| Caesarean section | 27(9.61) |

| Ever had complications at child birth | |

| Yes | 37(13.07) |

| No | 246(86.93) |

| History of treatment for | |

| STDS | 152(36.36) |

| Heavy bleeding | 23(5.50) |

| None | 243(58.13) |

| Any chronic medical condition | |

| Yes | 33(7.89) |

| No | 385(92.11) |

| Chronic condition suffered | |

| Hypertension | 8(1.91) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 2(0.48) |

| peptic ulcers | 23(5.50) |

| None | 385(92.11) |

Table 3: Obstetric and Gynaecological history of the 418 women of reproductive age in eastern Uganda.

Partner factors

We sought to understand the influence of partner influence on contraceptive uptake. We interviewed female that were staying with their partners.

In this study the mean age of partners was 23.17 (SD 18.59) with majority of the participant’s partners being in the age group of 30-34years.Moreover about 41.9% (113/270) of the partners were reported to have had secondary school education, with 63% being informally employed and majorly 87.8% (237/270) in monogamous family settings.

Significantly, although the majority of respondents, 75.6% reported that they decided on matters of pregnancy as a couple, only 68.5% of the respondents reported being supported by their partners on use of contraceptives. However, 67.4% reported to have ever been accompanied by a partner to seek contraception services. Moreover, only 44.8% reported discussing about health of a family member and family planning (Table 4).

| Characteristic | n(%) |

|---|---|

| Age of partner Mean± SD (n) | 35.57±9.59(270) |

| 20-24 | 19(7.04) |

| 25-29 | 45(16.67) |

| 30-34 | 78(28.89) |

| 35-39 | 44(16.30) |

| 40-44 | 34(12.59) |

| 45+ | 50(18.52) |

| Education level | |

| Primary | 77(28.52) |

| Secondary | 113(41.85) |

| Tertiary | 80(29.63) |

| Occupation of partner | |

| Formal | 100(37.04) |

| Informal | 170(62.96) |

| Partner drinks alcohol | |

| Always | 6(2.22) |

| Occasionally | 69(25.56) |

| No | 195(72.22) |

| Type of marriage | |

| Monogamous | 220(81.48) |

| Polygamous | 50(18.52) |

| Easily discusses with partner | |

| Yes | 237(87.78) |

| No | 33(12.22) |

| Health issues discussed | |

| Health of family members | 113(41.85) |

| Family planning (FP) | 4(1.48) |

| Both family health & FP | 121(44.81) |

| The person who decides pregnancy | |

| Both | 205(75.93) |

| Man alone | 26(9.63) |

| Woman alone | 39(14.44) |

| Partners support | |

| Yes | 185(68.52) |

| No | 85(31.48) |

| Discuss with partner about FP | |

| Yes | 182(67.41) |

| No | 88(32.59) |

| Accompanies partner to FP clinic | |

| Yes | 182(67.41) |

| No | 88(32.59) |

| Total | 270(100) |

Table 4: Partner factors and its influence on contraceptive use among 270 WRAG in eastern Uganda.

Contraception remains a key pillar in safe motherhood and sexual and reproductive health rights (SRHR).It helps avert significant maternal and perinatal and childhood morbidity and mortality and will be key to achieving sustainable development goals. This is vital especially in areas with restrictive abortion laws and patriarchal societies [10,11].

Contraceptive prevalence rate and choice

The contraceptive prevalence rate (CPR) in this study was 33.73% .The modern contraceptive prevalence rate (mCPR) accounted for 30.86% (129/418) while the traditional contraceptive prevalence rate (tCPR) accounted for 2.87% (12/418). This study demonstrated that as far as eastern Uganda is concerned, Uganda has failed to hit the target of mCPR of 50% (2020, 2017).

Furthermore, the CPR of 33.73% is lower than the 39% reported by the Uganda Demographic and Health Survey [12] and that in other studies in sub-Saharan Africa such as mCPR of 35.6% - 37.9% reported in Ethiopia [13,14], 39% in Kenya, 43% in Zambia [15], 36.9% reported in Ghana [16] and in Saudi Arabia at 45% [17]. The difference may be because of the differences in the methods used. The study in Zambia utilized the Demographic and health surveys data of 2014, and the ones in Ethiopia were largely community based.

Furthermore, some differences may arise due to cultural, religious and economic differences. In societies where polygamy is more acceptable due to either religious or cultural beliefs, women are less likely to use contraception as the more children a women produces, the more security in the marriage [17-20]. In addition to the above, men in these communities look at these many children as a source of fame and wealthy [19].

However the mCPR of 30.86% is higher than the 26.6% reported in a household survey study in Uganda by Namasivayam et al. [21], 21% reported a study in Ghana and 28.3% in Nigeria [22]. The differences would have resulted from the different methods used in the study. Namasivayam et al did household survey while in Nigeria and Ghana, only market vendors were respondents. This study focused on women from different backgrounds and occupations.

Moreover the mCPR of 30.86% in this study is lower than 34.9% reported by a study in Ethiopia [23], 38.6% in Kenya [24].These two other studies were carried out largely in urban areas. The study in Kenya further focused on slum and non-slum dwellers in the city while in this study; our population is largely rural and peri-urban.

Furthermore, the low prevalence could be explained by the health stem factors that are a common problem in Uganda, where facilities continue to grapple with stock-outs, unfriendly service providers, untrained personnel and poor organizational structure [25].

This study demonstrated that the most commonly used modern contraceptives were injectables (56.7%), implants (27%) while among the traditional methods, calendar method was topping. These findings are in agreement with a studies in Nairobi [26] that reported preference for injectables followed by implants, Ghana [27,28] and Ethiopia [14,23,29]. In a multicentre study in SS, injectables were most preferred followed by oral pills [30], while in Singapore, a study reported preference for condoms [31] and pills in United states of America(USA) and Europe [32], Bangladesh and Saudi Arabia [17,33]. Significant to note is that, the one of the studies in Ghana considered persons with the same occupation (market vendors) [27], while another used a case-control study design [28]. These differences may be explained by the fact that study participants in Europe, USA, Bangladesh and Saudi Arabia were more educated than those in our population. In addition, women in the west are more empowered than in our settings and therefore are more likely to be free when using pills than in the third world where women prefer a more private method.

This study found a lower rate of tCPR 2.87% compared to a study in Kenya [24] and the 4.9% reported in Bangladesh [34].The study in Kenya found that a high prevalence of traditional methods use was associated with living in a non-slum area. In this study, we did not study the influence of being or not being a slum dweller. Moreover, differences could have resulted from different lifestyles of dwellers in east Africa’s biggest city Nairobi and in Bangladesh in comparison to the majorly rural east of Uganda.

Moreover, 36.6 %( 124/418) women had ever used contraception in this study. This is higher than that reported in a study in Ethiopia that reported only 1.8% [14]. The major reason highlighted for stopping use was complications attributable to the contraceptives as reported by 50% of the respondents. On some occasions, this fear is unfounded and largely influenced by myths, misinterpretations and lack of right information from the right persons [19,20].

We further sought to understand the factors that influence contraceptive uptake. In this study, almost all, 99.8%, the participants had ever heard about and could name a contraceptive method. This finding as similar to studies elsewhere such as in Uganda [7], Nigeria [16,35], Ethiopia at 95.6% [14].

Mass media especially radio (91%) and health workers (82%) were the most common sources of information while internet source was low at 10%. The findings mirror those of a study in Uganda [7] and Ethiopia [14], Europe and United States of America (USA) [32] and in Saudi Arabia [17]. However in Ghana, a study reported television at 56.2% [27], while one in Nigeria reported friends, 33.3% [22] being the major source of information. Whereas friends are recognized as crucial sources of information especially in lowly educated communities, the accuracy of such information is queried [22].

In this study, 52% received information from television. Like findings in other studies [16,22,28], Television (TV) and radio can be important tools is dissemination of health messages. However in Uganda it is easier to use a radio than TV because of low number of people connected to the national electricity grid reported at 19% rural and 23% urban(USAID, 2020).

In Saudi Arabia, about 34.4% accessed information through internet compared to only 10% in eastern Uganda. This difference can also be explained by the fact that Saudi Arabia has a higher population (96%) connected to the internet, than Uganda (24%).These studies continue to underscore the importance of health workers and use of an easily accessible media putting in mind technical and infrastructural challenges in delivering right information about contraception. This will help plug the gaps created by misinformation, myths and misapprehension; all that discourage contraceptive uptake. However worth noting is that several studies have consistently reported negative correlation between widespread knowledge and awareness of contraceptives and utilization of same [36]. Fear of side effects, myths and misconceptions about modern contraceptives as well as service provider factors have been associated with the low level of use, despite the high knowledge and awareness levels [36] (Michelle J Hindin, 2014). Research has further shown that effective counseling does not only improve uptake but can also influence choice of a method [37]. Given that there is likelihood of a woman changing her contraceptive choice, it is necessary that she receives right information from the right persons to help her make an informed choice [38].

Age of the female was significantly associated with contraceptive use (p=0.043, AOR=3.75, 95%CI =13.48-0.48). The odds of using contraception increased with increasing age and the trend changed after age 30-34years .This may be because as one ages, fecundity reduces since there is reduced ovarian reserve and possible lack of sexual desire. Furthermore, such mothers may have attained their desired family size. This finding was similar to findings in Bangladesh [33] and Ethiopia [29].

Furthermore, the odds of married women using contraception were 2.9 compared to the unmarried ones. Moreover marriage was significantly associated with contraception use in eastern Uganda (p=0.001, AOR=2.94, 95% CI 1.56-5.54). A study in North west Ethiopia showed similar findings that married women were 5.88 times more likely to use contraceptives than unmarried (singled, widowed, and divorced) [29], and in other studies in Sub-saharan Africa such as in Kenya [24,39] and in Nigeria [35]. In this study, there was higher prevalence of contraceptive use among married, 30.6% (128/418) compared to their unmarried counterparts 2.9% (2/418). Similar to the findings in a study in Tigray in Ethiopia, the rate among married women was higher than unmarried ones at 41% [14].This may be explained by the fact that the married women are more likely to have untimed sexual intercourse compared to the unmarried ones and thus more need for contraception. Moreover a research done in Ethiopia showed that married women have higher odds of utilization of sexual and reproductive health services when compared to the unmarried counterparts [40]. However a study in Ghana on Ghana reported lack of association between a female marital status and age with contraceptive uptake [16].

One of the known factors that influence utilization of health services is education. In a multicentre analysis of Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) a decade ago of Ghana, Kenya ,Madagascar and Zambia, it was shown that net of all factors, education significantly influenced ones’ use of contraception [41].

However, neither the education level of the respondent nor that of the partner affected utilization of contraceptive services in this study. This finding is in line with findings in Ghana that reported that education status did not influence modern contraceptive uptake [16,27] and in Saudi Arabia [17]. This is in contrast to studies in Uganda [21], other parts of Sub-saharan Africa [24,33,35,39] and in Asia [33] that have shown that the more a woman is educated ,the more likely she will use contraception.

In most environments including Uganda, education is associated with empowerment and better household income. These factors improve access and use of health services. In a study done in Kenya, education was found to influence income and the later influenced contraceptive use rather than education per se [41]. We could not ascertain this influence in our study since household incomes were not included and education controlled for during analysis. This therefore would not support the argument that Universal primary Education (UPE) and Universal secondary Education (USE) work towards enhancing modern contraceptive use. Uganda’s education curricular has been in the limelight as one lacking in sexual and reproductive health components and population education. Several studies in Uganda have expressed dire need for Adolescent and sexual reproductive health education [7]. A case in point where such has had an influence is Iran, where population education is part of the curriculum at all educational levels, including university and colleges and students are required to take a two-credit course on population.

Women in the higher wealth quintile have ore odds of using contraception than ones in the lower wealth quintile [32,33,39]. These women are more likely to be more educated, empowered, formally employed and can easily access contraceptives [39]. In this study, formally employed women were 2.8 times more likely to use contraceptives than those in informal employment (COR 2.8; p=0.001). This is consistent with a studies in Kenya which showed that women working outside the home [24] or those in formal employment [39,24]. Childbearing and rearing is in some insistences incompatible with formal employment [24].

Although our finding discredits the differential in levels of education in the utilization of modern contraceptives, this may be because of other confounders since several studies have given credence to it. The influence of education on modern contraceptive use cannot be over-emphasized. This is because, as the level of education increases, wealth and prestige tend to increase and the intention to limit children in preference for career growth by using modern contraceptive will increase. Apparently, education leads to a greater ability to acquire wealth and prestige; this competes with decision on childbearing since in a modern economy children are for many years resource consumers rather than resource producers. This principle seems to apply as individuals especially women attempt to be upwardly mobile socially within a society, or as they try to prevent social slippage; a loss of social and economic status relative to others of the same cohort.

In a study in USA, “ever use” of oral contraceptives (OCs) among adolescents and young adults results in a greater likelihood of ever having sex, sexual transmitted diseases (STDs) and pelvic inflammatory diseases, pregnancy, and abortion compared with those adolescents and young adults who never used OCs [42]. Therefore, we anticipated that history of treatment for sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) would probably have influence on use of contraception. In this study, women who history of treatment for STDS were 1.98 times more likely to use contraception than counterparts with such a history and statistically significant (AOR=1.98, P=0.018, 95% CI=1.12-3.48). Likewise in Kenya, Lunani et al. [39] demonstrated that women who had ever tested for Human immune virus(HIV) were 1.52 times as likely to use contraceptives as women who had not tested [39]. By extrapolation, fear of STDs positively influences use of barrier methods of contraception.

Uganda’s total fertility rate (TFR) has been declining over time and has been marched with increasing uptake of contraceptives. TFR has declined from 7.4 to 5.4 children per woman between 1988-89 and 2016 respectively yet contraceptive uptake improved from 8% in 1995 to 35% in 2016 [12]. In order to study this factor, we sought to find out whether the number of living children did affect contraceptive uptake.

Women with three or more living children were 10 times more likely to use contraceptives than those with none children. Whereas there were increased odds of using contraception as ones’ family size increased, this effect was lost as the mother attained five children. On logistic regression, it became statistically insignificant. These findings echoed those by studies in Ethiopia [13,29], Ghana [16]. However, in disagreement with this finding are studies in Uganda [21], Kenya [24], Saudi Arabia [17] and Bangladesh [33].

In studies elsewhere, dwelling in an urban area has been shown to be associated with increased odds of contraception use compared to rural settings [14,30] and as such women in the latter have been found to have a higher total fertility rate(TFR) compared to the former. However this was not significant in our study. This may have been due to numbers not powered enough to study the variable but since health system factors were all insignificant, and urban residence is normally associated with accessibility and affordability, this significance may be due to wide spread availability and accessibility at even health centre IVs ,thanks to government and development partners efforts.

Age of the last child was a strong predictor for contraceptive use, women with last child’s age ranging between 2-5 years were 2.1 times more likely to use contraceptives than those with older child or younger child (AOR=2.13; p=0.019; 95%CI:1.13-4.02). Age was found to be a significant predictor in a study in Tanzania [43] though for a very short time interval .This is because the older the child, the more the woman experiences freedom and productivity and thus realization of the need to space children. Also more women appreciate the loss of protective Lactational amenorrhoea method (LAM) more at this stage.

Decision on when to have the next child played a significant role whether to or not to use contraception. Women who had planned to have their next child five plus years after a delivery were more likely to use contraception (AOR=2.83; p=0.015,95%CI: 1.22-6.58) which is similar to findings of a study among African countries. Women who had planned their pregnancy were less likely to have short birth intervals compared to those who did not want the pregnancy at the time of conception. This could probably be due to the fact that women/couples who plan their pregnancy may follow the recommendations for child spacing and therefore end up with optimal birth intervals.

In this study, the number of children the woman had did not affect her use of contraception. However other studies in Uganda [21], Kenya [39] and Malawi demonstrated parity as having a significant influence on contraceptive use.

In a study in Ghana among postpartum mothers, women who had undergone a caesarean section were 5 times more likely to use contraceptives than those with vaginal delivery or no delivery. Furthermore, in addition to the Caesarean delivery, women that had suffered complications during childbirth had more odds of using contraception. However, in this study these factors were collinear and therefore not included in the final model. The difference could have been the study populations used. Furthermore, caesarean section is in most cases more traumatic than vaginal delivery and advised against short inter-pregnancy interval much more emphasized in the former than the latter by health workers and so the more likelihood of such mothers using contraception.

A female that had a partner supporting contraceptive use was 5 times more likely to use contraception than counterparts without male partner support and was of statistical significance (AOR=5,P=0.0001,95% CI: 2.53-9.89). This finding is in line with other studies’ findings [14,16,19,27].This is reinforced in Uganda where males dominate decision making in reproductive health and their disapproval may spell doom for marriage. No wonder this was echoed in a Nigerian study that reported partner disapproval as a major barrier to contraceptive uptake [22].

Partner’s age was significantly associated with contraception uptake, with partners age increasing with age until maximum at 35-39 years (P=0.01, AOR=5.75, 95% CI 1.52-21.76.) and so is his support of the woman to (P=0.0001, AOR= 5, 95%CI= 2.53-9.89).This further reinforces the argument of male involvement in improving uptake of Sexual and Reproductive Health services. This finding is in agreement with those of other studies in Uganda [45] but also elsewhere that have reported positive correlation between male support and female contraceptive use [14,16,19] (Agnes Asiedua 2020; Allen Kabagenyi, 2016; Araya Abrha Medhanyie, 2017). In a study is Saudi Arabia, the odds increased till 36-45 years but male partner’s age was not statistically significant [16]. It is likely that such a male has probably reached the desired family size or is facing hardships of childhood support and is thus more likely to embrace contraceptive use than the young ones.

In this study, over 62% of the participants were Christians. Religion has been shown to influence contraceptive use in various studies [19] particularly when faiths have an anticontraception stance. However like in a study by Namasivayam et al. [21], it had no influence in this case. This is because women may have been able to subvert the various religious precepts to manage the size and well-being of their families.

In this study, the duration of marriage did not affect the contraceptive use. However, a study in South Africa Godswill et al. [45] reported that women in union of less than 5 years were less likely to use contraception and this had statistical significance. It is likely that shorter and longer duration into marriage are likely to coincide with the reproductive life and achieved desired family size respectively.

The study has presented evidence on the current trend of contraceptive use in the cosmopolitan eastern region of Uganda and thus the level at which the region is regarding the Uganda government commitment of achieving 50% modern contraceptive prevalence by 2020 during the July 2012 London conference. It has further highlighted the determinants of contraceptive use especially the role of male involvement in sexual and reproductive health, and the channels of communication that is effective to deliver the right information to the right population. This could have important implications for health policy and interventions on sexual and reproductive health in the area and other similar areas in Uganda.

As a cross-sectional study, we cannot infer causal interpretation of the results. The study relied on respondents’ self-reported data and could not be verified, which raises the issue of respondents’ recall bias and may have resulted in the over or under estimation of the study parameters although all quality assurance and ethics measures were employed in data acquisition and processing. Generalization of the findings of the study is also limited since we recruited respondents from a sample of women that had come to take care of the sick. Moreover, the information regarding the partners was collected from the second party (female partner) and accuracy cannot be guaranteed. However, the findings of this study can be considered indicative of the context considered.

The prevalence of contraceptive use of 33.7% was lower than the national average reported in the health and demographics survey. The mCPR of 30.86% was lower than Uganda’s target of 50% by 2020. These outcomes underline the need for interventions that emphasize practical education of both men and women to focus on the provision of information emphasizing the benefits of contraceptives services that go beyond a woman to the children, family and the nation at large. Furthermore, there is need to create awareness and knowledge about contraceptives, in order to demystify the misconceptions, misapprehensions and myths especially about modern contraceptives, and increase males’ approval of their use.

We are highly indebted to our study participants, the staff and management of Mbale Regional Referral Hospital .We would like to appreciate HEPI for supporting data collection.

Citation: Birungi Julian Daisy, Prossy Tumukunde, Rebecca Nekaka, Julius Nteziyaremye. Contraceptive Uptake in Eastern Uganda was the 2020 Target of 50% Modern Contraceptive Rate Achieved?. Prim Health Care, 2021, 11(4), 379

Received: 18-Mar-2021 Published: 30-Apr-2021, DOI: 10.35248/2167-1079.21.11.379

Copyright: © 2021 Nteziyaremye J, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.