Research Article - (2018) Volume 4, Issue 4

Objectives: The aim of this work is to examine the effects of the free care policy on the access, management and practice of cesarean section in Niger. The secondary data collected from the various health facilities as well as the national health information system made it possible to analyze the impact of the risk and organizational factors on the practice of cesarean section in Niger before and after this policy.

Methods: A panel analysis was conducted with the same data to determine the impact of this policy on the evolution of these factors and the likelihood of delivery by cesarean section in Niger. In these models, the need for Caesarean is justified by the existence of a medical matrix of gravity and a matrix of explanatory variables of organizational order. Two different models are estimated. The first explains the practice of cesarean section in Niger with data collected from all regions of the country. The second explains Caesarean section practice in the three regions that have a national maternity reference. The data collected covers the period 2006-2014. A total of 2,250 files were studied in the eight regions of the country.

Results: When considering only the period after free care, the results obtained indicate that the risk factors were less important in explaining the occurrence of a caesarean section than before. This is valid for both the medical severity variables and the organizational variables.

Discussion: These results confirm those of the statistical analysis in which the national rate of caesarean section has been observed to be changing, slowing down and declining.

Thus, alongside the policy of care for pregnant women and cesarean section, the State must also make efforts to improve the health card, the proper functioning of the care system to through the timely reimbursement of factors issued and the availability of human resources in quantity and quality to hope to achieve the objectives pursued through this policy.

Keywords: Free healthcare policy; Cesarean section rate; Organizational factors and risk factors

In Niger, cesarean deliveries have increased since 2006 with the beginning of the policy of free care [1], but unfortunately, the rate of cesarean section in Niger is still very far from the African average and the worldwide recommended standard by the World Health Organization [2].The annual reports of the Ministry of Public Health estimated this rate at 0.8% in 2005, against 2.8% and 3% respectively in 2009 and 2010. This rate dropped to 1.9% in 2016 [3].

The WHO recommended interval for caesarean rate in 1985 was 10%-15% [4], this higher estimate being confirmed by subsequent studies [5,6]. In its 2009 Handbook, the WHO acknowledged the existence of a growing body of research, showing the negative impact of a high rate of caesarean section and that very high and very low rates were dangerous, but there was no consensus on the optimal rate. They identified a lack of empirical evidence for an optimal percentage or range of percentages for caesareans [2].

However, the literature reminds us that medical practice is influenced by medical factors (the state of gravity of the patient, his age) and non-medical, including financial. Gruber et al. find that a large pay gap between cesarean delivery and vaginal birth accounts partially for the difference in practice [7]. Organizational motives, including the presence of a practitioner or clientele, also influence Caesarean practice. The completion of a caesarean section, while necessarily requiring a more qualified staff (anesthetist, obstetrician), allows a faster handling.

From a medical point of view, caesarean is justified when the patient presents certain risks, for example, aggravated hypertension or placenta previa. However, this practice has significant undesirable effects. The practice of cesarean increases maternal and perinatal mortality five to seven times [8] mainly due to anesthetic complications, puerperal infections and venous thrombolism [9].

A joint UNFPA and WHO [10] publication states that a maximum of 15% of the caesarean rate must be respected. Beyond this figure, the use of caesarean is considered abusive and would have a more negative than positive impact, considering the risks of this operation.

Dumont et al. estimated the expected rate of caesarean for pregnant women in West Africa. They report that the optimum rate of Caesarean is not really known to achieve the best maternal and fetal prognosis, especially in developing countries [11].

The objective of their study is to present a simple method for calculating a caesarean rate taking into account the obstetric risk of the target population; to test this method by estimating the expected rate in a population of pregnant women in West Africa. This is a population study of a cohort of 19,459 pregnant women monitored throughout pregnancy, childbirth and postpartum.

Yussif et al. analyzed free delivery through cesarean in Mali. They first recalled that in Mali, maternal mortality reached 464 deaths out of 100,000 births. In addition, less than 50% of women give birth in a maternity center. These trends result mainly from socio-economic factors: disproportionately, the poorest women have limited access to health care because of the financial barrier represented by the direct payment by the user [12].

Tinoaga et al. have shown that the effectiveness of the implementation of the free caesarean in Benin has helped to increase the caesarean rate from 2.38% in 2009 to 3.48% in 2012. Unfortunately, these results are correlated with a fatality case rate of caesarean to 9.9‰, inadequate information of the beneficiaries, not including some of the medicines in the kit, the payment by the beneficiaries for additional costs. They recommend an assessment in all of the country’s public hospitals to better identify malfunctions [13].

Witter studied free deliveries and caesareans in West Africa and Morocco [14]. Policies have generally been considered relevant and important. In some cases, they also seemed to be effective. However, the selectivity of these policies for caesarean purposes (in two of the four countries) has been problematic to some extent. Caesareans can save lives, but if use increases, it is difficult to know if women have received this care out of need (medical indication).

In Niger, the proportion of the state budget allocated to the health sector increased from 7.3% in 2005 to 9.3% in 2009. Maternity delivery has increased in urban areas to 70% 2005 to 83.1% in 2011 and 8% in rural areas to 17.5% for the same period. The decision made by the government of Niger to make free access to a certain number of health services for women of child-bearing age for pregnant women is one of the flagship measures that have actively contributed to the improvement of these services indicators.

The basic theoretical formulation of the demand for health is derived from the work of Grossman [15]. Among the determinants of this demand are costs of care, income, and individual patient characteristics. Later, it was shown that the quality of care and the queue are also critical in the demand for care.

Thus, the first studies that looked at the behavior of the demand for care following an increase in the tariffs of care concluded in favor of an inelasticity of demand in relation to price and income. The work of Heller [16], then Akin et al. [17] marked this discourse encouraged by the World Bank (WB) since it provided arguments for a cost policy that would affect little access to care of the poorest. But the work of Gertler et al. [18] from an estimation model different from the two previous ones will conclude in favor of a significant elasticity of demand with respect to prices.

In Niger, the high rate of maternal mortality is probably explained in large part by the inadequacy of this demand, especially in rural areas. It is therefore to remove this financial barrier and thus increase the demand for care by pregnant women that the government of Niger has decided to make health care free for pregnant women.

The objective of this research is to highlight the impact of free caesarean on the probability of delivery by caesarean in Niger public institutions.

Thus, the research will specifically be interested in checking on:

• The role of medical severity variables in the practice of caesarean in health centers in Niger,

• The role of organizational variables in the practice of cesarean in Niger,

• The response of reference maternities in the new policy of care of cesarean in Niger.

Later, this work will proceed as follows. In the next section, health statistics will be presented in Niger from 2004 to 2016 through stylized facts as well as the source of the data. It will be presented in section 3 empirical modeling, and Section 4 will present the results and discussion. Section 5 will present the conclusions and the implications of economic policies.

The data were extracted from birth registration registers at national maternity, district hospital and regional hospital levels throughout the national territory. These registers contain the details of all admissions concerning the woman’s state of health, her marital status, the type of childbirth undergone, the causes of Caesarean in the case of cesarean delivery and this is carried out anonymously. For the construction of the national database, the number of files examined by region is based on the percentage of women of reproductive age on the total population of women of childbearing age. The data collected include births before 2007, i.e., before the introduction of the free caesarean policy, as well as pre-natal and post-natal consultations, as well as births from 2007 to 2014. A total of 2250 files were studied in the eight regions of the country.

Figure 1 shows regional statistics on attendance at health centers by pregnant women. For each region between 2004, 2010 and 2016, the percentage of women of childbearing age in the total population was compared and the percentage of new consultations on the number of women of childbearing age.

The first ratio gives the importance of women of childbearing age to the total population of the region. The second ratio measures the accessibility of pregnant women to all women of childbearing age. It gives an idea of the chance of monitoring a pregnant woman from the beginning of her pregnancy to conclusion.

For the four regions in Figure 1, the percentage of women of childbearing age decreases for the three time periods selected (2004, 2010 and 2016). It also appears that the percentage of new consultations on the number of women of reproductive age to increase from 2004 to 2016.

Given that this percentage is very low in 2004 because less than 5% except Dosso (8%) this ratio has reached the average of 20% for all regions from 2010 except Agadez where it revolves round 17%. This reflects the abrupt effect of the policy of free care for pregnant women in these different regions.

For the four regions of the second figure, the percentage of women of reproductive age to decrease (except Tillabéry and Zinder who witnessed a small increase in 2016) for the three periods of time selected (2004, 2010 and 2016). Percentage of new consultations on the number of women of child bearing age to increase from 2004 to 2016. The second implication of the policy of free healthcare concerns the significant increase in the cesarean rate in Niger. The figure below shows the evolution of this rate from 2005 to 2016.

Since the beginning of the policy of free delivery of cesarean section, this rate has increased sharply to reach 3% of deliveries in 2010. Unfortunately, there is a sharp decrease in this rate and this may be related to several reasons. The main reason is undoubtedly linked to the accumulation of arrears of payment by the State with these care centers, which has resulted in a reduction in the benefits offered by distinguishing between scheduled caesareans and emergency cesarean sections.

On the other hand, the political instability experienced by Niger in February 2010 has not facilitated the mobilization of the resources needed for the regular supply of health centers by the Ministry of Health in accordance with the planned policy in maternal health.

Overall, the success of this policy of free access to care for pregnant women and cesarean is dependent on the availability of the necessary human resources in quantity and quality and this in each region of the country.

Table 1 gives us information on the percentage of women of childbearing age by region, the rate of caesarean by region, the percentage of the population living within a radius of less than 5 Km per region, the free policy by region and the amount of the reimbursements of the invoices of the free of charge care policy by region .

| Regions | Total Population | Women of child bearing (WCB) | (WCB)/(WCBT) | Caesarean section rate |

Population 0-5 Km |

Free Category of Care | Refund of free care (FCFA) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agadez | 546846 | 120691 | 3% | 4.90% | 67.68% | 26841400 | ND |

| Diffa | 683870 | 135033 | 3% | 1.91% | 42.59% | 49826980 | 69117150 |

| Dosso | 2206739 | 461089 | 12% | 1.20% | 46.68% | 91323600 | ND |

| Maradi | 3794379 | 737761 | 19% | 1.51% | 44.43% | 292494510 | 6090490 |

| Tahoua | 3821986 | 759830 | 19% | 1.03% | 48.20% | 318000279 | 5314940 |

| Tillabery | 2992139 | 628520 | 16% | 0.46% | 46.30% | 36772100 | ND |

| Zinder | 4076544 | 812652 | 21% | 0.92% | 39.01% | 293348800 | 8556040 |

| Niamey | 1131882 | 281052 | 7% | 16.83% | 97.79% | 2186328922 | 320000000 |

| Niger | 19251386 | 3936630 | 100% | 1.90% | 48.31% | 3294936591 | 409078620 |

Source: Nigerian Health Statistics Yearbooks 2016

Table 1: Demographic, health and financial data by region (Table 3 in the appendix provides more detailed information on the reimbursement of free healthcare from 2008 to 2014.).

The analysis of the demographic, health and financial data in this table reveals significant disparities in Niger between the regions in the implementation of the policy of free maternal care and cesarean. If these disparities are not internalized, they alone can compromise the success of this policy.

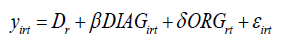

The econometric approach is based on a regression of the panel data where the dependent variable is binary and is represented by the different modes of delivery. It takes the value 1 if it is caesarean section and 0 otherwise. The objective is to examine whether the probability of giving birth by caesarean was affected by the policy of free cesarean in Niger. At the level of the different health centers that are involved in the constitution of this database, the results are measured at the individual level, so a basic model for modeling the probability of performing a caesarean is specified as follows:

In this case, y irt indicate if the th woman of the nth region had a caesarean section at period t. Regional fixed effects are controlled by ε iht .

DIAG is the set of diagnoses of the individual i, from region r, to period t such that one of them justifies the conduct of a caesarean. These dummy variables are: age of the parturient, antenatal surveillance, history of caesarean, arterial hypertension, preterm birth, placenta previa, poor presentation of the fetus, fetal distress, multiple delivery, transfer initiation, dystocia, premature rupture membranes, diabetes, eclampsia, and preeclampsia.

ORG is the set of variables giving the characteristics of the health center: number of obstetricians in the health center, number of anesthetists in the health center, number of midwives in the health center, number of gynecologists in the health center.

Finally, ε iht is the error term. In Niger, there are only three national reference maternities in Niamey, Tahoua and Zinder regions.

After the implementation of the maternal care and caesarean delivery system in Niger in 2007, these centers experienced a very significant increase in their activities. Being referral maternities compared to other district hospitals that also practice cesarean, they have certain specificities in terms of equipment, the availability and the quality of the caregivers which consideration can better explain the probability of delivery by caesarean, compared to other health centers in Niger.

It is assumed that the technical expertise and skill is higher and the health workers are of better quality in these reference maternities. The intent of this research is to verify the impact of the concentration of health personnel at these maternity clinics on the practice of cesarean in Niger. As a result, we have modified our model to better take into account the unobservable related to the three reference maternities (quality of obstetricians).

The modeling of the maternity characteristics of unobservable references is here in the form of a fixed maternity reference effect. To do this, we implemented a specified model as follows:

The variables DIAG and ORG are defined above, while the reference D m.refer refers to the reference maternity effects.

It is appropriate in this new specification to compare the probability of delivery by caesarean in maternity referral compared to all national structures on one side, to assess the importance of this probability between two types of structures after the implementation of the system of free maternal care and cesarean in Niger; on the other.

The outcomes of Model 1 and Model 2 estimates are presented separately in one table. The overall outcomes of model 1 (respectively model 2) are those from the data collected on deliveries in the periods before and after free cesarean delivery in Niger. The outcomes after the free model 1 (model 2 respectively) are those obtained from the data collected on deliveries only in the period following the free delivery of cesarean section in Niger. On Table 2, since the dependent variable is a binary variable, we present the estimates of the mean marginal effects of a probit model.

| Caesarean | Model 1 | Model 2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Global | Sample after free | Sample global | Sample after free | |

| Age | 0.006 | 0.004 | 0.0164** | 0.0127 |

| 0.005 | 0.005 | 0.006 | 0.197 | |

| long and difficult childbirth | 2.918*** | 1.243*** | 1.224*** | 2.149*** |

| 0.311 | 0.284 | 0.261 | 0.573 | |

| Hypertension | 3.139*** | 1.635*** | 1.893*** | 7.921 |

| 0.591 | 0.362 | 0.409 | 2.168 | |

| Premature delivery | 2.153*** | -1.653 | 0.695 | -5.162 |

| 0.665 | 0.639 | 0.606 | 1.619 | |

| The child has a bad position | 2.700*** | 2.680*** | 1.839*** | 7.872 |

| 0.396 | 0.514 | 4.18 | 2.91 | |

| The child is big to pass normally | 3.0192*** | 1.390*** | 1.454*** | 7.807 |

| -0.652 | 0.406 | 0.41 | 3.2308 | |

| Multiple childbirth | 7.593 | -3.386 | 3.493 | -7.766 |

| 0.724 | 0.548 | 4.991 | 9.0014 | |

| Placenta covering which prevents the passage by the low way | 1.927*** | 1.182*** | 1.482*** | 1.606*** |

| 0.393 | 0.329 | 0.517 | 0.526 | |

| History of caesarean section | 2.092*** | 1.540*** | 7.382 | 7.779 |

| 0.417 | 0.382 | 1.698 | 1.973 | |

| Diabetes | -1.225 | -6.589 | 6.398 | -6.281 |

| 1.638 | 0.808 | 1.55 | 4.145 | |

| Violent and involuntary contraction of muscles | 6.387 | 0.444 | 6.997 | 7.115 |

| 0.396 | 0.425 | 1.523 | 2.0053 | |

| Decrease of the oxygen of the child | 1.157*** | 1.538*** | 7.06 | 11.751 |

| 0.442 | 0.444 | 1.404 | 2.154 | |

| Crushing of the umbilical cord | 7.213 | -5.672 | 5.11 | -0.657 |

| 0.773 | 0.986 | 9.247 | 1.806 | |

| Antenatal surveillance | 0.576 | 1.356*** | 0.309 | 0.327 |

| 0.402 | 0.412 | 0.354 | 0.536 | |

| Number of anaesthetist help | 0.318*** | 0.311*** | 0.085** | 0.155*** |

| 0.027 | 0.035 | 0.398 | 0.0562 | |

| Number of surgeon help | 0.0531* | -0.0959 | 0.067*** | 0.026 |

| 0.0279 | 0.032 | 0.021 | 0.026 | |

| Number of midwives | 0.018*** | 0.035*** | 0.003* | 0.0055 |

| 0.003 | 0.004 | 0.002 | 0.003 | |

| Constant | -3.563 | -3.773 | 1.948*** | -0.571 |

| 0.746 | 0.863 | 0.541 | 0.667 | |

| Standard deviation in parenthesis (***) significant at 1% (**) at 5% (*) at 10% | ||||

Table 2: Results of model 1 and 2 estimates.

Outcome of the model 1

In these models, the need for Caesarean section is justified by the existence of a medical matrix of gravity and a matrix of explanatory variables of organizational order. The results of the estimation show that the medical severity variables (patient characteristics) are almost all significant at 1% with the exception of multiple births. This Outcome translates for the whole country that the higher the frequency of these different cases, the higher the probability of Caesarean.

The importance of care management policy is that it encourages women to consult regularly even in the absence of financial resources and especially encourages them to give birth in health facilities. The increase in the frequency of prenatal consultations makes it possible to detect very early a possible problem in the normal course of pregnancy. This situation makes it possible to predict Caesarean section in time, which explains the relevance of all these variables of medical gravity.

The Outcome of the estimates taking into account global data and those taking into account the collected data were compared only after free maternal care. Medical severity variables overall; significantly and positively explained the probability of caesarean with global data. But comparing with the outcomes of the data collected after free care, we find that the explanatory power of these variables decreases for almost all variables. According to Mohamed, et al. the factors most strongly associated with the occurrence of caesarean (positive relationship) in Morocco are the number of births greater than or equal to 4 deliveries, the hypotrophy and the age range between 21 and 35 years old [19].

Regarding the impact of organizational variables on the practice of cesarean in Niger, with the adoption of the Caesarean delivery system, the outcomes are globally debatable. Among these variables we can note the number of midwives in the health center, the number of anesthetists and the number of surgeon assistance.

Overall, these results indicate that the probability of having a caesarean is higher in institutions with specialized quality and quantity. Regarding the number of anesthetist and surgeon assistance, the results are similar to those of the medical severity variables. That is, their explanatory power in the justification of a caesarean is less important during the period following the implementation of the maternal care management system.

These undoubtedly appreciable results can be further improved if the State makes even more effort in the reimbursement to the health facilities of the bills sent as a result of the acts of care. Currently the average of these refunds is around 40% from 2008 to 2016.

This delay in reimbursement in invoices issued can severely limit the scope of this policy of free caesarean section in Niger and thus jeopardize the main objective, which is that of the reduction of maternal mortality in Niger.

Outcome of model 2: Reference maternity level model

The outcomes of Model 2 support, as a whole, the explanation of the probability of delivery by caesarean according to the two matrices of explanatory variables before and after the implementation of the maternal care management system and the cesarean section in Niger.

It is expected that the probability of giving birth by caesarean section will be much more affected respectively in the three referral maternity hospitals in Niger than in all the health care facilities (district hospitals) combined.

The comparative analysis shows us that despite a net increase in attendance at these health care facilities (Figures 1 and 2) after the implementation of this reform, the results of model 2 (global) do not reveal not a predominance of this probability compared to those of model 1 (global data).

The comparative analysis of the results of model 2 (after free care) compared to those of model 2 (global data) do not seem to show the impact of this reform on the probability of giving birth by caesarean section in maternity hospitals. Niger. These results indicate that the likelihood of cesarean delivery was little or not affected in referral maternity hospitals.

The aim of this policy of free admission was above all to increase the number of births by caesarean, an alternative to increase the cesarean rate compared to normal deliveries. Through the global outcomes of the estimated parameters, we can conclude that this policy of free maternal care and cesarean section did not have a significant impact on the probability of delivery by cesarean in Niger.

These outcomes were confirmed even when the sample of women was limited to the three regions with a maternity reference (model 2). From the fact that a low rate of caesarean in the short and medium term is associated with significant maternal and infant mortality in developing countries, and thus the health of mothers and children, these outcomes call for appropriate economic policy implications.

In this sense, significant and constant efforts must be made to significantly increase the rate of cesarean in Niger despite the policy of free maternal care and cesarean. These efforts go through increased training in quantity and quality of organizational variables or provision of care (midwife, surgeon, assistant anesthesiologist). Ensuring the regular functioning of health centers through the regular supply of these centers for medicines, or the payment of bills within the time limit following orders for medicines by these same centers from health centers. purchase of pharmaceutical products.

The region of Niamey which reached a caesarean section rate of 16% with 97% of its population which is located on a radius of 0 to 5 Km. In other words, to improve the state of health of the population and especially to benefit In addition to the policy of free maternity care and cesarean section, the state still needs to review its health card by bringing the population closer to the structures of health care offers. The rate of 16% cesarean section in the Niamey region is correlated with the ratio of doctors/inhabitants, nurse/inhabitants, midwife/woman of childbearing age, as well as the number of anesthetist and surgeon assistance (Table 3).

| District hospitals | Mother and child health center regional maternities of references regional hospital centres |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Years | Average amount issued | Average amount reimbursed | Repayment rate | Average amount issued | Average amount reimbursed | Repayment rate |

| 2008 | 1073600000 | 691600000 | 64% | 760000000 | 624000000 | 82% |

| 2009 | 1339200000 | 403200000 | 30% | 920000000 | 732000000 | 80% |

| 2010 | 2312000000 | 101082672 | 4% | 1000000000 | 464000000 | 46% |

| 2011 | 1465200000 | 187500000 | 13% | 3132000000 | 424000000 | 14% |

| 2012 | 1904000000 | 184500000 | 10% | 944000000 | 516000000 | 55% |

| 2013 | 1441800000 | 516000000 | 36% | 1084000000 | 161200000 | 15% |

| 2014 | 2128000000 | 448500000 | 21% | 856000000 | 4307520 | 0% |

| National hospital | Total | |||||

| Years | Average amount issued | Average amount reimbursed | Repayment rate | Average amount issued | Average amount reimbursed | Repayment rate |

| 2008 | 186000000 | 186000000 | 100% | 2160004158 | 1556191082 | 72% |

| 2009 | 461000000 | 461000000 | 100% | 2908081213 | 1624711082 | 56% |

| 2010 | 504000000 | 504000000 | 100% | 4115597080 | 1090869566 | 27% |

| 2011 | 358000000 | 167000000 | 47% | 5241709321 | 848467984 | 16% |

| 2012 | 906000000 | 544000000 | 60% | 4172388746 | 1261113198 | 30% |

| 2013 | 1076000000 | 226000000 | 21% | 3948988859 | 935355714 | 24% |

| 2014 | 1254000000 | 0 | 0% | 4606892655 | 477029810 | 10% |

Source: National Institute of Statistics (INS, 2015)

Table 3: Indicators of the reimbursement situation of structures from 2008 to 2014.

Thus, in order to succeed in its policy of raising the rate of cesarean in Niger, the political authorities must link the policy of free maternal care and caesarean with a policy of training and the allocation of the necessary and qualified human resources in all other regions of the country.