Journal of Multiple Sclerosis

ISSN - 2376-0389NLM - 101654564

Research Article - (2025) Volume 11, Issue 4

In this report, we present a case of visceral leishmaniasis in a patient with multiple sclerosis (MS) under fingolimod treatment. We discuss the previously published cases of MS patients under different immunosuppressant therapies to highlight its risk in endemic areas and suggest a therapeutic approach.

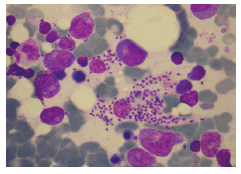

A 33-year-old man with relapsing-remitting Multiple Sclerosis (MS) and no other relevant medical history was admitted to our hospital because of fever. After a diagnosis of MS in 2011, he had been initially treated with glatiramer acetate and then with Interferon Beta-1a. Due to clinical and radiological activity, treatment was switched to fingolimod in 2013, achieving disease stability. He had lived in Barcelona (Spain) and had no history of recent travel over the past 10 years. He referred to fever up to 40ºC, chills and abdominal pain localized in the right upper quadrant during the previous week. He did not have neurological symptoms. At admission, the patient had a temperature of 37.6ºC, other vital signs were normal. Physical examination revealed tender hepatomegaly and splenomegaly with no adenopathy, jaundice, or additional findings. Laboratory test results included a hemoglobin concentration of 11.5 g/dL, leukocyte count of 1260 cells/μl, platelet count of 59.000 cells/μl, 0.81% of reticulocytes, Lactate Dehydrogenase (LDH) of 742 UI/L, total bilirubin of 2.12 mg/dL aspartate aminotransferase (AST) of 297 UI/L and Alanine Aminotransferase (ALT) of 205 UI/L, Gamma-Glutamyl Transferase (GGT) of 187 UI/L and Alkaline Phosphatase (ALP) of 115 UI/L. A peripheral blood smear did not show immature cells or schistocytes. An abdominal computed tomography was performed, revealing an enlarged liver without focal lesions and homogeneous splenomegaly of 16 cm with no other remarkable findings. Given the suspected diagnosis of opportunistic infection, fingolimod was withdrawn. Blood cultures were negative, as well as serology for hepatotropic viruses, parvovirus, Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV), and blood cryptococcal antigen. Realtime PCR for Leishmania spp was performed in two blood samples and bone marrow biopsy and all of them were positive. In the bone marrow sample, Leishmania amastigotes could also be observed (figure 1). A diagnosis of visceral leishmaniasis was established and the patient received treatment with liposomal amphotericin B at a dose of 4 mg/kg body weight once daily for five days followed by five weekly doses for a total dosage of 40 mg/kg. After treatment of the infection, the hemogram progressively recovered. As the patient presented negative anti-John Cunningham virus (JCV) antibody, MS treatment was restarted after 5 weeks by switching fingolimod to natalizumab neither leishmaniasis nor MS relapses after 6 months of follow-up.

Figure 1: Bone marrow aspiration: we observe intracellular and extracellular amastigotes of leishmania.

Leishmaniasis is a protozoan granulomatous disease endemic to South America, South Asia, Africa, and Mediterranean Basin. The disease is transmitted by phlebotomine sandflies and is caused by species of the genus Leishmania that are phagocytosed by macrophages and proliferate inside mononuclear phagocytic system cells. Clinical severity of the disease ranges from asymptomatic infection to disseminated forms of the infection with high morbidity and mortality depending on the characteristics of the parasite and the host response [1]. In this regard, it is well-known that immunosuppression considerably increases not only the risk of severe clinical forms but also predisposes to reactivation and impairs response to treatment [2].

Most of the literature about leishmaniasis in immunosuppressed patients focused on persons with HIV infection [3], even so, there is also a rising number of reviews and case reports of patients with rheumatological, gastrointestinal, and dermatological conditions requiring immunomodulatory drugs, including glucocorticosteroids [4], cytostatic agents (i.e. methotrexate and purine analogs) [5] and TNF-⺠inhibitors [6] as well as solid organ/hematologic transplant recipients [7].

MS treatment has changed considerably over the past 25 years with the advent of new Disease-Modifying Therapies (DMTs) [8]. DMTs induce immunomodulation and depletion of T or B cells, providing not only higher efficacy but at the same time new clinical challenges, as an increased risk of infection. It has been suggested that Th1 cells and T central memory cells would play a particularly important role in the host defense against Leishmania spp. [9]. Among the waxing body of literature dealing with infectious risks in patients with MS under DMTs [10], there are only a few cases reports that have addressed specifically the issue of leishmaniasis. After describing another case of visceral leishmaniasis in a patient under treatment with fingolimod, our case arises the question about the risk of developing severe clinical forms of leishmaniasis in patients treated with DMTs.

Sphingosine 1 phosphate receptor modulators, such as fingolimod, avoid migration of CCR7-positive T lymphocytes such as CD8+ naïve, central memory, and Th17 and Th17/Th1-helper cells out of the lymph nodes, but also impairing cellular immune response and TNF alpha production [9]. Three cases of leishmaniasis have been reported in patients under treatment with fingolimod; the first by Artemiadis et al. presented as visceral leishmaniasis in a 37-year-old woman from Greece who was treated with fingolimod for 29 months. A blood qPCR was positive for Leishmania infantum and the patient was treated with liposomal amphotericin B, with complete response to treatment [11]. The second, reported by Hernandez Clares et al. was a 32-year-old woman from Spain receiving fingolimod for 25 months who presented aggressive cutaneous leishmaniasis by Leishmania infantum in the form of granulomatous infiltration of the outer ear accompanied by painful cervical adenopathies. Intralesional treatment with amphotericin B was attempted unsuccessfully, requiring intravenous liposomal amphotericin B [12]. The last one reported by Williams et al. was a 61-year-old man from Australia receiving fingolimod for 6 years who presented visceral leishmaniasis by Leishmania infantum probably acquired after a trip to southern Italy [13]. In all cases, prolonged lymphopenia attributable to fingolimod was observed, which is presumably associated with an increased risk of infection progression. Here, we report another case of visceral leishmaniasis in a patient under fingolimod treatment for 7 years and grade III lymphopenia, supporting the hypothesis that fingolimod treatment would increase the risk of more aggressive forms of leishmaniasis.

Glucocorticosteroids, among other mechanisms, reduce T-lymphocytes and derived cytokines, which are the main host defense against intracellular microorganisms like Leishmania, which may promote the development of visceral leishmaniasis, as well as chronicity and relapses in these patients. Murine models have demonstrated an association between continued exposition to CS and an increase in amastigote burden in the spleen. In different series of cases and case reports of leishmaniasis in CS-treated patients, diagnostic delay, clinically severe disease, and partial response to treatment were observed and likely attributable to the steroid therapy [4,14].

Azathioprine, although barely used nowadays, is a purine analog that blocks de novo synthesis of purines and induces apoptosis of Tlymphocytes. It has been reported to increase the risk of developing bacterial, viral, fungal, and protozoal infections. Although no cases of leishmaniasis have been published in MS patients on azathioprine treatment, two cases have been described, one with Crohn's Disease and the other with midline granulomatosis [5,15].

Alemtuzumab, an anti-CD52 monoclonal antibody, is thought to decrease the number of circulating B and T lymphocytes and their subsequent repopulation, although the exact mechanism of action is still unknown [16]. Infections have been described in patients with alemtuzumab, mainly involving the respiratory and urinary tract [10]. Even though leishmaniasis has not been reported in patients with MS, one case was published in Italy in a patient with chronic lymphocytic leukemia [17].

Rituximab is an anti-CD20 that produces B cell depletion through various mechanisms. Some cases of visceral leishmaniasis have been described in patients with lymphoproliferative disorders under treatment with rituximab and there is evidence that its activity is not restricted to B lymphocytes, since it also may reduce the activity of both peripheral and tissue-resident T lymphocytes [18]. However, in patients with lymphoproliferative disorders, rituximab is often used in combination with other drugs and we must also consider the contribution of the underlying disease to the total immunosuppression [19]. Hence, the real risk of opportunistic infection may be lower when used alone as DMT in MS. About other anti-CD20 antibodies, neither ocrelizumab nor ofatumumab has been related to leishmaniasis. However, its limited use compared to rituximab should be considered.

No visceral leishmaniasis cases have been reported for patients under treatment with glatiramer acetate, natalizumab, teriflunomide, and dimethyl fumarate or deoxyadenosine analogs as cladribine and mitoxantrone, although they also modify cellular immunity. For interferon-beta, not only has not been observed an increased risk of specific infections but also a protective effect against Leishmania have been described depending on the dosing and treatment protocol used.

Liposomal amphotericin B has proved to have the best safety profile and interesting evidence of its efficacy in immunosuppression patients (6). One of the major concerns is the reintroduction of immunosuppression. Considering the information, it seems reasonable to choose alternative DMTs with a lower risk of recurrence, such as natalizumab ensuring close clinical follow-up and blood qPCR. The proportion of MS individuals treated with fingolimod that develop aggressive forms of leishmaniasis remains low, hence it does not appear reasonable to completely avoid its administration. The case we report, on the same line as the previously described, highlights that treatment with fingolimod should be done carefully in areas endemic for Leishmania spp.

In patients from endemic areas under treatment with any of the mentioned DMTs presenting fever, cytopenia, or organomegaly it is worth considering leishmaniasis to avoid delayed diagnosis. Early withdrawal of the DMTs and rapid confirmation of the diagnosis, so that systemic treatment can be started in the shortest time possible are critical for the management of such cases.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Citation: Nicolau PB, et al. Leishmaniasis in a Patient with Fingolimod-Treated Multiple Sclerosis: Infectious Challenges of Disease Modifying Therapies. J Mult Scler, 2022, 9(7), 451.

Received: 11-Mar-2025, Manuscript No. jmso-21-48280 ; Editor assigned: 14-Mar-2025, Pre QC No. jmso-21-48280(PQ); Reviewed: 28-Mar-2025, QC No. jmso-21-48280(Q); Revised: 30-Mar-2025, Manuscript No. jmso-21-48280(R); Published: 04-Apr-2025, DOI: 10.35248/2376-0389.24.11.04.451

Copyright: 2022 Nicolau PB. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.